By Kevan Garecki

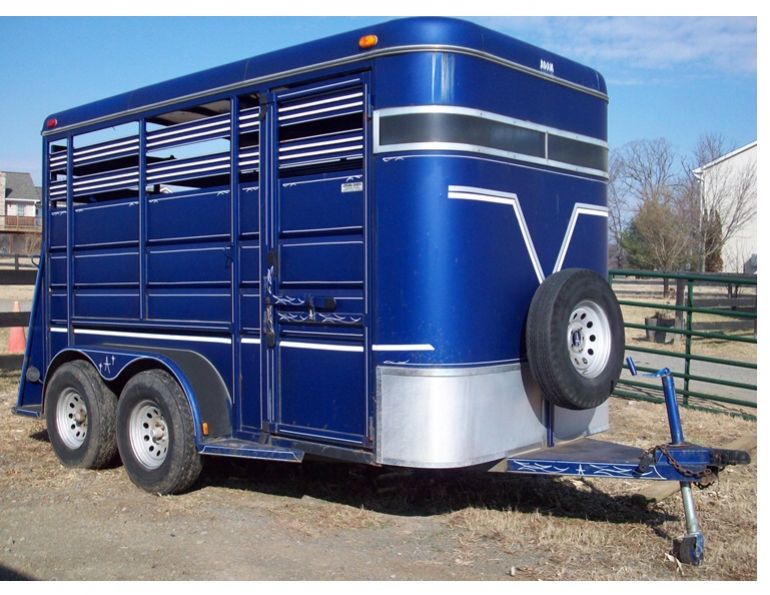

The use of larger horse trailers has become more common as many farms and training operations increase their volumes, and coaches and barn owners resort to hauling their clients’ horses to events — some as part of a value-added courtesy, while others may charge for the service. There are a number of considerations when dealing with “heavy trailers,” which is how most horse rigs are classified, not the least of which is how the vehicles and drivers are licensed. While there are provincial anomalies, the rules are similar across the country. Larger trailers may require additional or provisional licensing. I welcome this level of legislation, as it helps ensure those towing the larger units have learned at least the basics of towing and have had their skills tested in a formal setting.

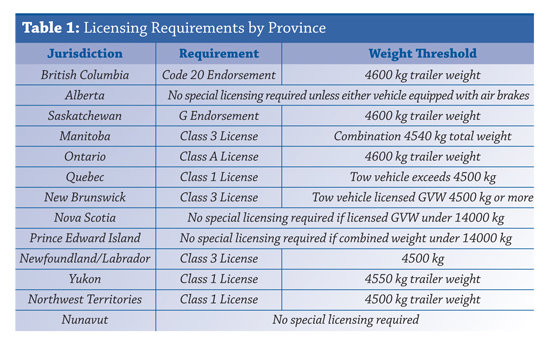

Most jurisdictions have a weight threshold beyond which the operator must obtain the correct class of license before driving the combination on a public road. Attaining this additional weight usually requires the vehicle owner to apply for and obtain a National Safety Code (NSC) number. The NSC program is in place to increase the operational safety of commercial trucks and the carriers registered under the program may be required to submit to safety audits to ensure their practices are in keeping with national standards.

There are a very few exceptions, but their uses are very narrow in scope. The most common exception is the use of farm plates on tow vehicles. This type of licensing has very specific uses that most horse transport circumstances do not fall under.

Some provinces do allow for the transport of horses under common farm policies, but not if the vehicle is being used for hire. Farm plates restrict the vehicle to be used only for commerce directly related to the operation, such as a breeder hauling their own stock.

Many seemingly private moves are actually commercial transport, including coaches, trainers, and boarding barn owners hauling their clients’ horses.

Clarifying “commercial service” is important, as many seemingly “private” moves may actually fall under the heading of commercial transport. Generally, the law stipulates that any time anything or anyone is moved and the operator receives consideration or compensation for that move, it is considered “commercial.” Therefore, a trainer hauling a client’s horse to a show is performing a commercial movement, because the trainer received some sort of compensation for the training and the trip to the show is considered part of the trainer’s service. A barn owner taking their boarders for a trail ride may be fall under the same category because they charge board for the horses they are moving. Even a move that is compensated by barter may be looked upon as commerce.

When it comes to transporting horses other than their own, all professionals share a similar responsibility to their clients: to provide safe, legal, and humane treatment for those horses. To do so may require more than meets the eye and a little homework!

The first consideration should always be for the horses’ safety, which includes ensuring that rigs and those driving them are legally operated. Most provinces have adopted legislation requiring drivers towing heavy trailers to hold commercial licenses or specific endorsements and have classed them within the realm of commercial operation, so the driver must submit a medical report subsequent to a knowledge test and practical assessment of their skills. Those jurisdictions imposing special licensing for heavy trailers have made the qualifying process relatively simple, making the endorsements easily attainable for most drivers.

A caveat for those who would scoff at these rulings is that the failure to properly license and insure the tow vehicle, trailer, and driver can void the basic insurance on the entire combination and may impact policies held on the individual horses. In the event of a crash, regardless of who is at fault, the operator and vehicle owner can be exposed to lawsuit. If a police officer determines a driver is improperly licensed, he may elect to impound the vehicles until a driver who holds the correct class or endorsement can move the rig legally. This type of situation is well known to the commercial law enforcement community, who frequently target heavy trailers through spot checks and random inspections. Corrective measures can range anywhere from a simple warning for a “first offence,” to impound, monetary penalties, and even license or insurance suspensions.

Table 1 outlines the requirements by province. The licensing programs are constantly changing and the information here was current at the time this article was written; but as with any other aspect of driving, the onus is on the vehicle owner and driver to comply, so inquire with your provincial motor vehicle authority before hitting the road!

A common misconception is that if the truck is not licensed over the GVW (gross vehicle weight) at which special licensing is needed, the need can be avoided. Such is not the case and in fact can cause even a minor incident to spiral hopelessly out of control.

Here are two real life examples of what can and frequently does happen:

- A barn owner had been trailering his clients’ horses for some time and was involved in a minor crash which was not his fault. However, since neither he nor his rig were properly licensed, all insurance was voided, even the policies on the horses in the trailer at the time. The resulting lawsuits put him in such financial hardship that he was forced to sell his farm to pay the costs.

- A lady decided commercial transport was a great way to make some extra money. After operating for several months, she was pulled over in a routine vehicle inspection and when the officer discovered the truck was not properly licensed, nor did she hold a license necessary to operate it, the rig was impounded. She had to arrange to have the horses moved out and correct the licensing issues before she could get the rig back. The entire process took over two weeks and the resulting gossip put her out of business.

With only minor differences in some jurisdictions, the licensing aspects of trailering should be approached thusly:

The first consideration should be for the total laden (loaded) weight the tow vehicle is likely to attain. Be generous on this figure and leave extra room in case you end up carrying horses that may need to go on a diet, a few extra bales of hay, more ribbons and trophies than expected, extra tack and passengers, etc. The licensed GVW of the tow vehicle must be equal to or greater than the total weight of the truck, trailer, and its projected full load.

Trying to “license light” is a common attempt to circumvent entering the commercial realm, but it is quite simply illegal to operate any vehicle on a public road when that vehicle or combination thereof is overweight, either by design or licensed GVW.

Common utility plates are only applicable under provincial weight limits and only for pleasure and recreational purposes. Farm plates, if they will cover horses, are limited for use of transporting the owner’s own stock only in instances directly related to the farm operation.

If the trailer is to be used commercially, then it too must bear the correct plate. The more common utility plate is not sufficient for commercial operation in most provinces; the only instance where such a plate can legally be used is when the trailer is under provincial weight limitations for its use and is operated solely for personal or recreational purposes. That excludes virtually every trainer, coach, boarding barn owner, and any other business from hauling their clients’ horses, and most certainly may not be used by a commercial hauler.

Here is a simple example: let’s take a three-quarter ton truck pulling a three-horse gooseneck trailer. The average three-quarter ton would likely tip the scales around 3400 kilograms and even a relatively light three-horse gooseneck will add at least 2700 kilograms. For ease of figuring, let’s take an average weight of 600 kilograms for each horse, but hay, water, and other supplies can easily add another 500 kilos to the mix, bringing our total payload to 2300 kilos. So the minimum safe weight the tow vehicle should be licensed for is 8400 kilograms. Take note that the individual weights of the truck and laden trailer are well within the requirements for special licensing in most provinces! For those who would take their rigs into the US, the ceiling for private operation down there is 10,000 pounds, or roughly 4600 kilograms, so driving this combination in any state will require adherence to US commercial regulations.

This additional licensing also has significant costs associated with it, not the least of which is regular annual inspections on the trailer and semi-annual inspections on the tow vehicle. Remember, we’re considered the same as any other commercial vehicle, so we must be able to prove we’re maintaining our rigs just like the big guys have to!

The best source of collective information should come from a local insurance broker who is well versed in commercial operations. They will know what you will need to operate legally in your home jurisdiction, but make sure you tell them where else you may be likely to go. Just because a rig is registered in Saskatchewan does not mean it doesn’t need to meet other requirements once it leaves that province. This is but one reason why commercial haulers charge what they do: it’s expensive to keep those rigs properly maintained and licensed correctly.

A shift in awareness in the livestock transport industry may affect aspects of how we move our own horses privately.

A long-awaited shift in awareness is upon the livestock transport industry and may even affect some aspects of how we move our own horses privately. Alberta has introduced new legislation that now affects all aspects of the relocation of any type of livestock, while BC has ramped up their enforcement procedures aimed at regulating livestock transport in that province.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has governing power over commercial livestock movement and handling, and their officers have the power to stop and inspect any conveyance containing animals.

In 2007, a comprehensive program was launched via a joint effort between industry, government, and other stakeholders in the livestock industry. This program is aimed at standardizing handling and offering training in “best practices” of most aspects of livestock care. The Certified Livestock Transporter’s (CLT) program is now embraced by most federal and provincial enforcement communities, and is even held as a standard by which the courts levy judgments upon violators. The CLT course is an inexpensive and comprehensive method to help those in a commercial capacity handle and care for the animals in their charge using industry accepted norms. At present, the CLT program is voluntary, but a movement is under way to make this program mandatory at a federal level. Many producers, processing plants, feedlots, and even sale barns and large auction yards already require drivers to be CLT certified before they can load or unload at their facilities. When the program does become mandated, it will encompass commercial horse transport as well.

The take home message is: If you’re going to do it, do it right or not at all. The result will be a safer environment for our equine friends and safer roads for the rest of us!

Main photo: Clix Photography - Any commercial trailering operation or rig exceeding provincial weight requirements, no matter the size of the trailer, is considered the same as any other commercial big rig vehicles.