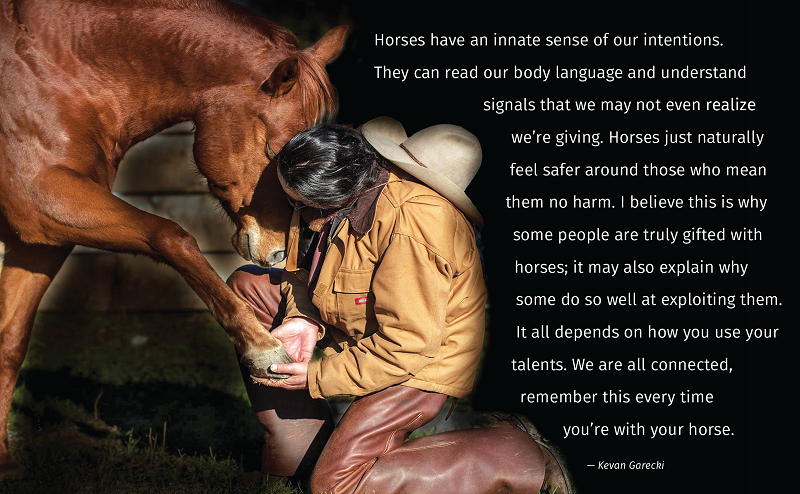

By Kevan Garecki

If you spend enough time around horses, before long you’re likely to encounter an injury. Some folks joke that they could bubble-wrap their horses and put them into a round room, and they’d still figure out a way to hurt themselves. Like humans, there are some horses that cruise through life without a single incident, while others just seem prone to elevate our stress level, and diminish our cash level, with frequent new and interesting injuries. There just might be more to this than meets the eye, however, as creating a safe environment for our horses actually begins with how we perceive them. I’m sure just about everyone who owns a horse loves that horse, and I’m not going to get into who cares more for their horses because of what they do for, to, or with them. I am going to share with you how we can increase understanding by the way we approach our relationship with horses, and enhance their safety as a result.

I’ll say one thing first, because a lot of people have a rather skewed perception of just what “training” is. You don’t “train” a half-ton flight animal that could kill you in the blink of an eye; you prove to him that he can trust you more than his own instincts. That is true horsemanship.

Bella casually investigates a trailer for the first time. There was no pressure, it was just an invitation. Photo: Lexi Jones

No matter what we ask the horse to do, regardless of the disciplines we pursue, when it comes to teaching or training, we all use operant conditioning to get that horse to do something. Operant conditioning is simply causing or coercing a specific action or response by varying the consequence. An example is the “pressure and release” method whereby a horse learns to move off our leg not by pressure, but when we release the pressure, thereby signalling that the horse has done what we’ve asked. Another example of operant conditioning is what trainers like to refer to, and all too often rely on, as “negative reinforcement”; the horse fails to comply with what we want and gets a smack for his trouble. Negative reinforcement, even pressure and release forms of training, are not centered around inviting the horse to learn; these methods are instead focused on shortening the training period, thereby getting the horse to do what we want sooner or faster. I believe this is a byproduct of our “instant gratification” culture: Not only do I want it, I want it right now! This might be okay for buying a television and taking a vacation, but it just doesn’t work as well for our horses.

Using pressure-free methods may take considerably longer, but in my experience these methods consistently yield far more positive and permanent results. Here’s an example: For many years a client of mine has routinely asked me to introduce trailer loading and transport to every one of her young horses. We typically begin this procedure as early as is practical, oftentimes loading the dam into the trailer with her month-old foal, so baby gets used to the idea of hopping into a dark, scary cave long before it’s ever dark and scary. On occasion, I’ve had to work with yearlings my client purchased that have been transported to her place, and most of them have varying levels of fear about trailering. This is where that shortcut approach no longer looks as expedient as it did when we were trying to rush that horse through her training by force. Now I have to start from scratch and wait until the horse understands that he no longer should expect negative reinforcement or fearful tactics, and the process takes a lot longer than it would have had we simply allowed her to learn at her own pace to begin with.

Trust is neither owed nor automatic – trust must be earned. Safety, however, should be automatic; the horse should never be put in a position where he has to earn the right to feel okay. Unfortunately, this very premise is at the heart of virtually every commonly-accepted training method in use today. So-called “natural horsemanship” techniques still utilise fear and pressure as operant modifiers – the stick with a flag or bag attached to it being an example. If the horse does not perform according to our wishes, we flap the bag, directing the horse otherwise. That is not communication, it’s fear-based habituation; the horse complies because of his fear of the bag. Another example is one I see all too often: shaking the lead rope to get the horse to back up. This is one of the worst examples of training, and only instils fear of pressure and discomfort. We shake the rope, it’s uncomfortable, and so the horse tries to avoid the sensation and retreat to safety. The horse learns to do this only when we stop shaking the rope, thereby proving that there is no learning going on; we are simply teaching the horse how to evade.

Young and fearful, this filly thought that anyone with a rope meant to harm her. It took a while before she understood that wasn’t necessarily true. Photo: Lexi Jones

Here’s a hint about this technique: If the horse has to raise his head, that means he’s uncomfortable. If you have to make the horse uncomfortable to get him to do something, what you’re really teaching him is just how much he needs to fear you.

When a horse is afraid, he resorts to one of two alternatives: flight or fight. Push a horse enough and that horse will quit trying to flee, and will instead oppose the force violently purely as a matter of survival. If you have pushed a horse to that point, you have long since lost any semblance of teaching or communication. If a horse is actively avoiding you in a session, step back and determine what action you took to cause that horse to be afraid enough to make him feel that he needed to flee the situation. It may not be that simple; the horse may have been conditioned long before by fear- or pain-based training that set him up for failure. Every time we use fear or pain as a modifier, we mortar yet another brick into the wall that horse is building in order to feel safe from us. The longer or more ardently this continues, the more intensely the horse feels at a loss. Eventually, the horse is labelled as “bad,” and the “training” level is increased until he either succumbs or explodes. Either scenario means the horse gets hurt, sometimes more emotionally than physically. When the psychological damage becomes too great for a horse to bear, frequently their emotions are switched off in an effort to cope, and we’re left with a lifeless body that complies because there’s just nothing else left to do. This is the same target for most torture-based interrogation techniques; the prisoner is pushed to the point of utter surrender, at which time they quite literally become mindless participants with no control over themselves whatsoever. Which would you rather stand beside – a thousand-pound friend who’s there because he enjoys your company, or a thousand-pound animal standing there only because he’s afraid of what you’ll do to him if he doesn’t? Which one could you trust in a pinch?

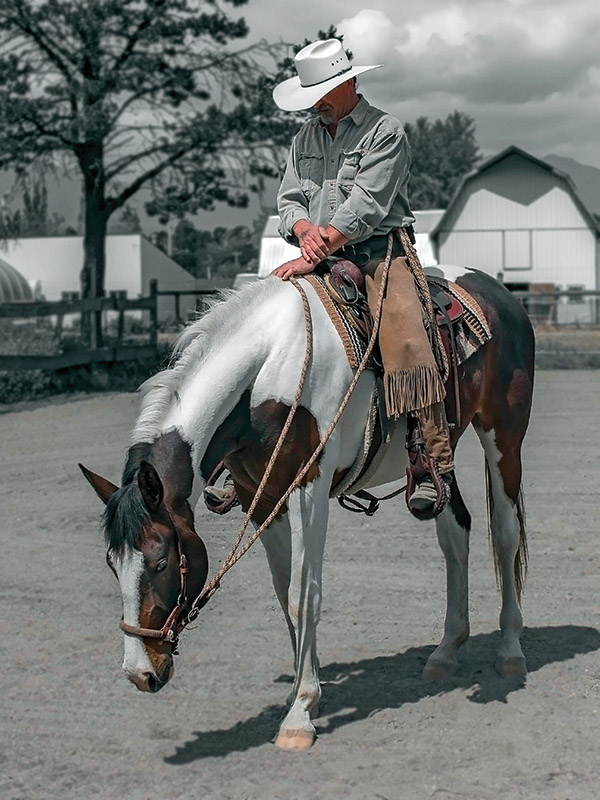

This is my first ride on Twiggy, a filly belonging to Martha Drennan of JMR Pintos. Thanks to more listening than talking, this was as crazy as it ever got. Photo: Lexi Jones

One effect of training principles that utilise fear or pain is that the horse becomes unnecessarily reactive, afraid of just about everything. A horse like this will continually injure himself and is often unfairly thought of as a “klutz” or a “wingnut,” when all it would have taken is patient understanding and a respectful approach in the beginning to allow that horse to feel safe, and to maintain a reasonable level of trust in humans. I think back to when I first encountered Noel; due to the torment he endured he was not just afraid, he was unreservedly terrified of virtually everything around him. (See The Story of Noel, The Christmas Pony.)

To Noel, doorways were daunting, human presence was horrifying, and in the first few weeks we worked with him he was even afraid of his own hair as he shed out! I consulted my friend, Jonathan Field, and as we discussed Noel’s case, we had to accept the grim possibility that this may be a horse so spiritually damaged that we had to at least consider the option of putting him down, as it was questionable whether he would ever be confident enough to function in a domestic world. It took a long time for Noel to gain the self-confidence he needed, and the results of that time are still at work today.

We took our time with Noel, allowed him to learn on his own terms, and never restrained or forced him into anything he wasn’t willing to do by himself. The results seemed to take forever, and there were countless setbacks, but over time we eventually began to see Noel gain the confidence he needed. As a result, that little horse went on to become first a liberty horse for Field, then a trusted mount for a lady who exposed him to trail obstacles, cow work, and many other disciplines. Her remarks to me some months after owning Noel were of amazement – not only did Noel display virtually no fear with new experiences, he eagerly anticipated them. This is what patient consideration can do, and what fostering an environment of security can offer a horse. This is not training, this is learning – there’s a big difference between the two.

This photo was taken during a photo shoot I did for my dear friend, Lisa Diagneault. I was trying to demonstrate a pose I wanted her to attempt, and as I did so her horse Thia simply placed her foot into my hand, pressed her head gently to mine, closed her eyes and released a big sigh. Thia and I have a great deal of history together, and by that gesture it was obvious that she certainly felt the need to share something. I was honoured and humbled that she chose to share it with me. This is a horse who trusts me, because she knows I trust her. This is why I do what I do. Photo: Lisa Diagneault

A horse that feels safe will respond rather than react. A horse treated with respect will reciprocate by trusting his human counterpart, and that’s a recipe for success on any terms.

Many years ago, I had an Arabian stallion that could throw me and some of the best riders I’d ever met, and he did so in a heartbeat. We all thought he was certifiably insane, and many of my friends thought I was just as crazy for keeping him. I tried every form of control imaginable, trying to enforce my authority over that horse. But every layer of force I added just made him that much less controllable. I finally traded him straight across for a Paint mare with navicular issues, and he transformed almost overnight. His new human did not try to contain his energy, instead she allowed him to use his talents, and proved to him that it wasn’t about control, that theirs was a partnership. I learned a great deal from watching them, and that Paint mare taught me more than did a few hundred other horses put together. I doubt that I would have been able to assimilate her lessons had it not been because that stallion first proved to me that force doesn’t work; it creates a horse that feels unsafe and is dangerous for both of us. Oh, and he also taught me how to fall off, and reinforced that lesson frequently!

That mare became one of the best friends I have ever encountered because by the time she arrived I had learned that I needed to do a lot more listening than talking. And because I was outweighed five-to-one and possessed a fraction of the strength of a horse, I was humbled into realizing that I didn’t need to be tougher than that horse; I needed to be tougher than whatever problems I had in dealing with her.

This is indicative of virtually every encounter I have with a horse, including my own. First, we quietly introduce ourselves, as is the polite way. I believe this sets the mood for the entire session. Photo: Lexi Jones

I receive numerous invitations to “fix” one horse or another, and invariably I discover that the problems are almost always caused by someone who neglected to listen, moved too fast, or used too much force. All of these things have created a horse that now feels unsafe, and more often than not has become injured as a result. It’s a great feeling to work with such a horse and show him there’s another way that doesn’t require fear or pain. I secretly smile when I see the horse’s owner look on in wonder at how well their horse is suddenly behaving! In addition, I secretly hope that the owner learned as much from those sessions as their horse did, because the more often I get to show someone how this works, the less often I will need to “fix” another horse.

An even better boost, though, is when I get to meet a horse that’s a “a blank slate,” one that hasn’t had to experience the ravages of fear and pain designed to batter them into submission. Those horses are wonderfully rewarding to work with, to see and utilise their natural curiosity, and watch them blossom with confidence! Interestingly, horses that have been allowed to maintain fearless, respectful relationships are seldom afraid because they’ve learned that we are not to be feared, and that every now and then we can actually be counted on to make an intelligent decision. This is a much better deal for both the horse and the human.

I’d like to invite you to evaluate your own techniques, really dig down into what you do and how you do it. Be fearless in what you’re prepared to see. Ferret out those misconceptions; remove the actions that cause fear or pain and replace them with respect. Instead of using a bag or a stick, discover how to use your body language to invite the horse. In many situations, responses can be solicited by simple redirection of your own energy – instead of using conventional pressure and release, we can use our own energy, often unwittingly, for better or worse.

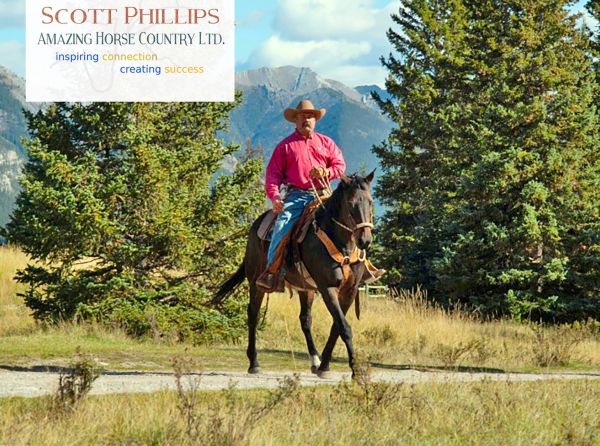

Pressure-free methods take longer but yield more positive and permanent results. Photo: Imagery by ManeFrame

I’m very fond of a saying that goes: Your energy introduces you long before you ever speak. Horses are attuned to this energy, and they are highly adept at reading it. Quite often, we will set our horses up for failure before we’ve even entered the barn, and some folks might be a little surprised to learn that their horses are probably more aware of their human’s mood than the human is.

I recently assessed a pony on behalf of Circle F Horse Rescue, which I now manage. Part of the assessment process involves basic yields and ground manners. These are simple exercises, but they can speak volumes when read correctly. In turn, I ask the horse to drop his head, back up, and yield the hind and fore in both directions; all of this is done with the least amount of pressure possible. I start by simply pointing my finger at the horse, and with my energy asking him to move. This pony did so quietly and politely, indicating that he was aware of what I was asking, and complied without fuss. No big deal, right? Did I mention the pony is blind in one eye, and that I purposefully began the exercise on his blind side, just to see how he’d react? How did he know what I was asking if I didn’t touch him? Simple: He responded to the energy I exuded – irrefutable proof that this works! Horses respond far more favourably to focused energy than they do to physical pressure, and a measurable portion of their behaviour is an ardent appeal to us to listen to their needs and communicate in a fashion that is productive and respectful.

Trust must be earned. Photo: Imagery by ManeFrame

This will open up a completely new field for some people, as it not only flies in the face of just about everything we’ve been taught about working with horses, but it just sounds kinda “crunchy” – you know, all granola, sandals, and hairy armpits – but that’s what people once thought about electricity, internal combustion engines, and the shape of the earth.

I’d like to leave you with a poem I wrote many years ago, which has become one of the most often requested prints from my gallery. I call it, Make Me Worthy Of My Horse.

Main photo: Lisa Andrews