By Jonathan Field

You are who your friends are. That adage can apply to horses, too. How we treat them will often be reflected right back at us — for good or bad.

Sometimes the difference between a harsh cue and an appropriate one can be subtle. Pressure can be effective, but intensity and timing can make all the difference. The concept of Hold and Wait helps horses and riders remedy incorrect use of pressure. It certainly helped me take my own horsemanship to the next level.

While the following exercises should result in your horse doing what you ask with added responsiveness, it won’t really be because you’ve taught him something new. Instead, you’ll have learned how to ask more effectively and clearly for what you want. And, the better you do it, the more you can expect in return.

The basic idea of Hold and Wait is to apply the least amount of pressure as possible and wait for a yield to happen. If you need to, incrementally increase pressure to get the yield, but don’t create a defensive brace with shoving or pulling.

I see horses that defensively brace against pressure all the time. While colts just getting started can have this issue, I see it a lot with established riding horses who have an ingrained pattern of behaviour with their riders.

Think about it. During the days, months, and years a horse interacts with us, he will need to make thousands of yields from our cues. If we give him poor feel and timing with our aids, he will learn to brace and become pushy to protect himself from discomfort.

Related: A Good Minded Horse

However, if we have learned the concept of Hold and Wait, the horse will soften and melt when these yields are asked of him — both physically and mentally. We can set him up to be more athletic, agile, and quick to respond. Plus, he will become less obstinate and herd-bound. And, it’s amazing how fast you can turn around most of these horses.

The Dance

For the purposes of this article, we’ll assume that your horse has been ridden for months, or most likely, years. He has the basic idea of yielding to pressure; but maybe his turns, stops, and yields to you are sluggish or braced against you.

Whenever we make contact with the horse either directly or with an aid — the touch of a rein or leg, moving him around for grooming, picking up his feet, loading him in a trailer, or backing him out of our space — we introduce a pressure of some sort. How we apply the touch is really important. In each of these everyday interactions, he is gauging the best way to be comfortable. Knowing that, we can influence his actions.

A horse can come to two conclusions to relieve pressure: yield away from it, or find a way to resist it. This resistance may manifest in many ways, including avoidance, rushing into you, bracing, and becoming pushy, among others. Whatever his method of resistance, our goal is to make yielding away the easier option, so he’ll choose it. The basic technique to do this is the Hold and Wait.

It’s like dancing with someone who’s not a very good dancer, but is excited to get around that dance floor. They push and pull their partner, and end up going faster than the other person. Their partner ends up braced against them, and has three options: leave the dance floor, put up with them, or teach them how to dance better.

In our dance, the two partners are the rider and the horse. It’s our job as riders to not create a situation where the horse feels that he has to brace because he’s being shoved or pushed. If we practice patience and do not get ahead of our horse, he can stay in time with us. So, the easiest option is to yield, and the dance flows.

Related: My Horse Bucks!

The Nose Knows

It is easiest to learn the lesson of Hold and Wait on the ground first. As demonstrated in Figure 1, back the horse up with your fingertips placed on his nose: fingers on one side, thumb on the other, above horse’s nostrils.

FIGURE 1

Here, I’m holding a steady feel on my mare, Tessa, and not pushing. In return, she is accepting of my request to move, and is relaxed in doing so. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

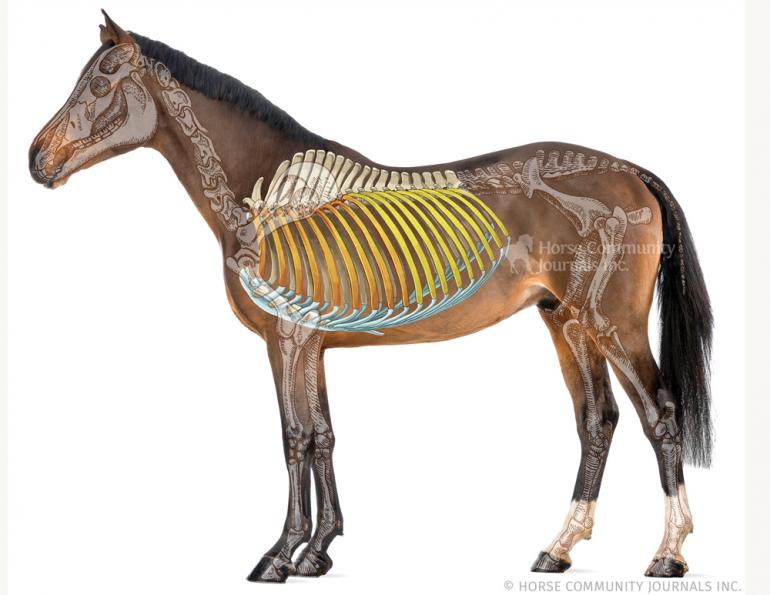

While asking Tessa to yield her head with a lateral bend, notice I’ve fixed my hand by resting it on her neck. If she were to pull against me in response, she will only feel as much pressure as she applies. I won’t accidentally add any more pressure, because with a set hand I can’t pull more against her. I simply keep my hand steady and when she bends toward me, she’ll give herself slack. Note: I won’t ask for more lateral flexion than Tessa is demonstrating here. Any more flexion might be too difficult for her, and it’s important to respect your horse’s physical limitations. Photo: Angie Field

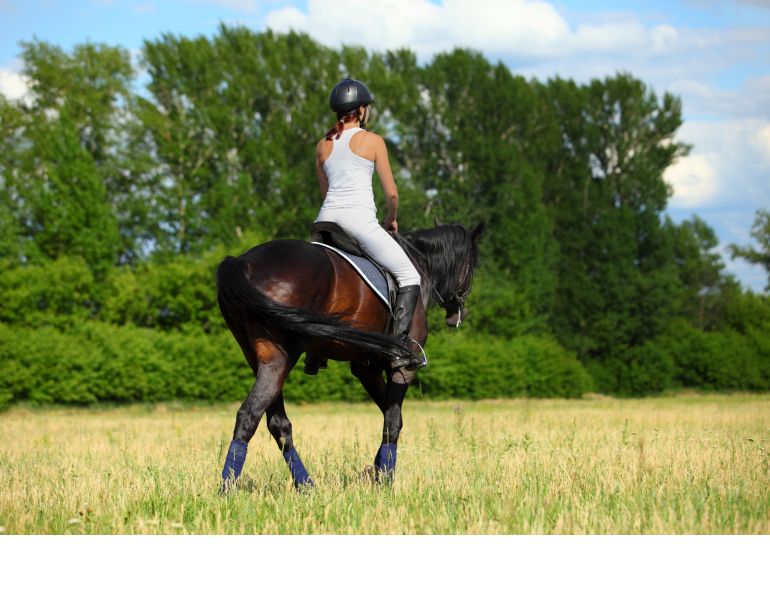

I’m preparing to ask Tessa to Hold and Wait with a back-up. You’ll notice she is still stepping forward, but beginning to slow because she felt me shift my weight back in the saddle. I’ve also prepared her for the hold by picking up my hands, although there is no tension in the reins yet. It’s important in this transition to not apply a hold quicker than Tessa can stop and change course. She is waiting for her cue, listening softly on this rope hackamore, and it would be unfair to pull on her face when she’s physically incapable of doing what I ask. But if I wait a moment more, her forward momentum will be gone and she’ll have her weight rocking back into a stop. That is the time to cue my reins and hold for her to shift that stop into a backup. Photo: Angie Field

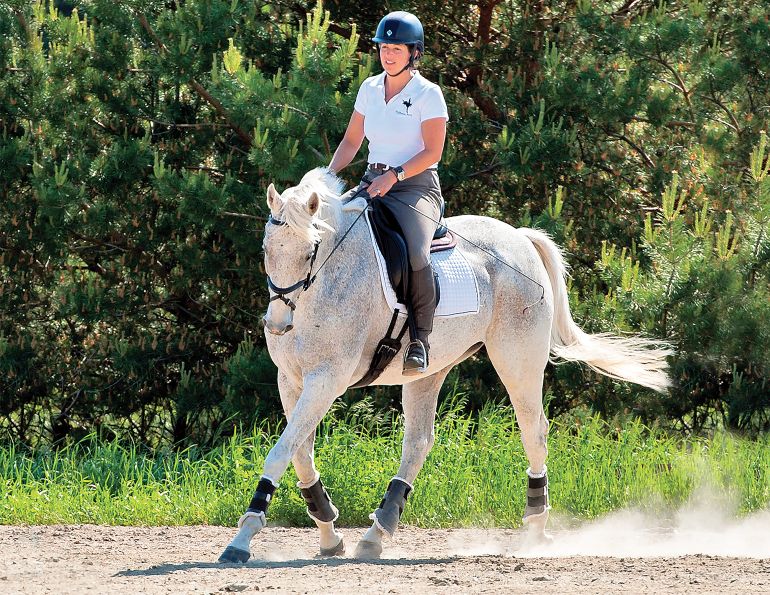

Lateral movement exercises can be fun and very good for horses to develop flexibility and strength. The key with Quincy here is to allow him to have a sense of relief as he moves over to his right. It’s too easy to leave the leg aid on, which takes away motivation for a horse to move over freely. As your horse moves away, make sure you give comfort for each step. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

Start with a small amount of pressure, much less than you’d think you’ll need to back the horse up. When the horse doesn’t respond to your cue, squeeze your fingers and thumb closer together, creating just a bit more pressure. Increase the level of pressure until you see the horse move off it. Watch for him to rock his weight back or take a step back. As soon as either happens, release. Now, we don’t have to hang up the phone and totally let go of the nose, but there should be a definite release of all the pressure to tell the horse he is going in the right direction.

It sounds easy, but if your horse is one that braces, he may respond in some interesting ways. Usually, I can tell if a horse has been pushed around because he will try to flick my hand away by flipping his nose. Or, sometimes, he’ll shoot forward into my hand, applying his own pressure. He’ll almost try to beat me to the punch by reacting with one of these moves just as I start to reach for him. If that happens, I have to hold my hand steady until the horse realizes that the answer is to step backwards. And with each footfall backward, he will soon realize the pressure is a little less, and he gets a little more release.

It sounds simple, but I’ve seen some horses who at first didn’t want to be touched on their nose at all become relaxed in minutes. You’ll see them become soft in their eye, flex through their poll a little, bring their head down. The change can be quite remarkable if they don’t get pushed by the handler.

Related: Restarting Halo, with Jonathan Field - Part 1

Under Saddle

We advance Hold and Wait by transferring the lesson to the horse’s back. Under saddle, we apply the idea in two more areas: with our legs and reins.

Reins – A direct, backwards pressure is one of the harder ways to teach a horse to yield to pressure, especially, if you use both reins. This lesson goes a bit smoother if you practice it first with a single rein, directing a horse into a simple lateral yield. That exercise is well known. What isn’t as understood is how to do it for maximum effectiveness.

Just like backing the horse on the ground, we have to learn to hold steady pressure with a rein, to not jerk our horse’s head to the left or right, and to respect our horse’s individual physical limits. For example, a horse may learn to brace because he is really committed to going left, but the rider suddenly pulls the rein hard to the right without warning. Or, the horse has yielded as far as he can manage, yet the rider is still pulling. Both of these examples are a recipe for creating a horse that braces when you pick up the reins.

Sensitive horses will get really worried and develop anxiety about requests they can’t perform. Less sensitive horses will reason that they couldn’t have responded to the cue anyway, so why bother trying anymore? This makes them get really dull to any aids.

That’s when people find themselves shopping for a bigger bit or trying to fix issues that actually have their root in the fact that the rider was incorrectly applying pressure, instead of holding and waiting. Having the patience to not get ahead of the horse gives time for their feet to catch up.

Related: The Horse Whisperer Generation

Legs – In the saddle, you also have leg pressure to consider. I commonly see riders apply a leg to move a horse off sideways, but when the horse takes that step away, the rider doesn’t release. Instead, that leg hangs on there and goes with the horse. Because there was no release of pressure or comfort, the horse comes to the logical conclusion that moving off leg pressure was the wrong answer. So, the horse dulls to leg pressure or gets overly anxious about it.

Sadly, I’ve even seen riders who are so unconscious of their leg use that they literally wear hair off the horse’s side because they continuously grind away at their horse. If this is your issue, the first step is self-awareness. The better feel you develop, the better you will practice Hold and Wait.

When I ask a horse to yield to a leg cue, if he moves at first even slightly I will release. It doesn’t matter if my end goal is side-passing him clear across the arena. With pushy ones, I count one step as a victory and reward the effort. Even if the release is only a small amount of pressure off his side, he gets the sense that he has moved off this pressure.

Fixing Tough Cases

I see a lot of horses that have already built up major defenses. These horses are well-versed in the ways they can fight pressure. The moment I pick up a rein, they try to push through it. I apply my leg, they shove into it and brace up against it. Or, I go to put my hand on their nose, and they either flick my hand away or run at me with pressure to beat me to it.

It’s important to not blame horses for these reactions. Remember, foals aren’t born with all that brace. The mare didn’t teach it to them. Human handling did it; it’s a learned behaviour to protect themselves from pain or discomfort. And we owe them the effort to try to fix the problem. The good news is, if we can cause bad habits, we can surely reinforce good ones, even for horses with very entrenched defenses.

Ideally, you apply the cue and incrementally increase pressure until the horse responds, and that’s that. But how do you handle it if your horse meets your pressure with pressure of his own? You continue to Hold and Wait. The trick is to not let him make you lose ground and push you around. There are times when I’m leaning hard into a horse, and it looks like I’m applying a lot of pressure, but the pressure is actually coming from the horse, not me.

We have to know the difference between pressure we initiate, and pressure coming from the horse. If it’s from the horse, we have to meet him with a nearly equal amount of pressure back at him, or at least for the length of time he pushes. How will he learn to yield from it if we back away from him first? This is its own type of hold, but the moment the horse backs away, the release needs to be there.

Say I’m riding a horse and put my right leg on to ask him to move left, but instead, he shoves into my leg and steps right. I don’t release pressure until the horse comes off my leg and is roughly back to the spot where I made the request. For a bystander, it may look like a lot of pressure coming from my leg, but actually it was the horse pushing on himself, and when he came off that pressure, he released it himself.

Then, we reset to zero. I ask the horse if I can move him over, instead of him moving me. If we can establish that baseline of moving off pressure even an inch, that’s a big deal for horses who have learned to protect themselves by bracing. I want the horse to feel the relief of that space.

The next time your horse braces up, gets pushy or pulls on you, remember these Hold and Wait lessons. They really can turn around a nervous or dull horse very quickly, because we are setting them up for success.

Related: Treats for Horse Training

Related: More Fun! And Why it's Important