By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

When it comes to purchasing hay this year, John Bland says, “[Horse owners] are between a rock and a hard place. This year, there’s typically nothing to cut.” Bland is a member of the Alberta Forage Information Network and has been producing and selling hay in Alberta for over 40 years. He says this year’s drought covers the majority of North America’s Great Plains region, so is different from other dry years such as 2001, 2009, and 2019 when droughts were more regional.

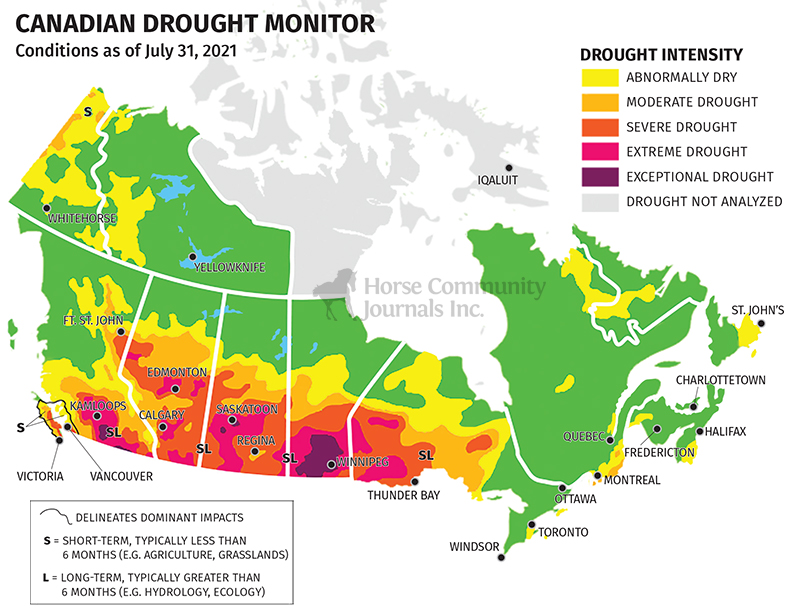

The drought has been nationally recognized, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has identified regions of drought — where forage yields were less than 50 percent of long-term averages — across Western Canada from British Columbia to Ontario. As of July 31, 2021, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Canadian Drought Monitor reported: In July, well-below normal precipitation and record-breaking temperatures rapidly worsened drought conditions across Western Canada, from Vancouver Island to Northwestern Ontario, resulting in significant and widespread impacts. Above normal temperatures followed the unprecedented high temperatures of early July, which led to drying surface water supplies, reduced streamflow, drying pasture and rangeland, negatively affected crops, and increased wildfires.

Provincial crop reports summarized similar conditions with the July 27 to August 2, 2021 Saskatchewan Crop Report, finding that hot, dry conditions had resulted in reduced pasture growth in many areas. By early August, 19 percent of Saskatchewan pastures were rated in fair condition while 81 percent were considered to be in poor or very poor condition. Impacts in British Columbia and Alberta were slightly better depending on the region, while Manitoba and northwestern Ontario fared slightly worse. By August 2, 2021, impacts on hay quality were moderate, severe, and extreme across the majority of Western Canada.

The lack of hay and poor pasture conditions concerned many and cattle ranchers were selling approximately four times the usual number of stock at auction in late July due to lack of feed. “People are desperate. It is a tough year, and it’s going to continue to be a tough year,” says Bland. “We’re going into fall with every pasture in the country overgrazed, which doesn’t bode well for next spring.”

This year, Bland harvested only 20 percent of the hay he typically produces in the Calgary area, but across Western Canada, hay supplies are variable. In British Columbia and Alberta, some areas had reasonable weather while regions around Grande Prairie and south towards Edmonton were significantly drier; however, there were definitely hay shortages in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Chris Fulkerth, a Professional Agrologist and past Chair of Alberta Forage Industry Network Board, says that means equestrians need to purchase hay sooner rather than later and should be prepared to pay more this year, too.

For those just purchasing hay now, “paying more” may mean paying double the usual cost for their hay. Bland reported that hay typically priced at $150 per ton increased to upwards of $300 per ton in mid-August. Unlike cattle, which can survive on a variety of feeds, horses must have good quality hay.

Related: Hay, Haylage and Silage: What's the Difference?

Unfortunately, this year’s drought conditions, hay shortages, and high hay prices may not be a one-off event. Canada’s climate is warming two times faster than the global average, and across Canada the frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme events like heat waves, wildfires, and floods are projected to increase. According to the 2020-2021 Regional Perspectives Report led by Natural Resources Canada, Canada’s changing prairie climate will result in more frequent extreme precipitation events, shifting precipitation patterns, increased water scarcity, longer growing seasons, and more frequent and intense droughts, all of which affect pasture productivity, quality, and nutrients — as well as future hay supply. Although hay productivity may increase in the near term, high temperatures, droughts, and more variable precipitation will negatively affect crop yields such as hay production over the long term. For example, model simulations for the years 2040 to 2069 for timothy hay crops in Edmonton and Fort Vermilion, Alberta; Melfort, Saskatchewan; and Dauphin, Manitoba indicate that first cut hay production will increase by 24 percent while second cut production will decrease by over 30 percent. The 2021 drought may be a harbinger of things to come, and horse owners would be wise to plan for future hay supply uncertainty.

Some of the ways to plan for that uncertainty are by improving pasture management, considering supplementation, altering feeding methods, increasing hay storage capacity, and pre-ordering hay from suppliers. Activities such as seeking out additional grazing areas, as well as irrigating, collecting manure, mowing, strip grazing, and fallowing fields to maintain good quality pasture could reduce hay needs. Utilizing hay cubes, pellets, or different types of hay to fulfill a horse’s forage needs could reduce the effects of fluctuating hay supplies. Feeding methods that limit waste and prevent over-feeding, such as using feeders and nets, can ensure that hay supplies are well-utilised. Increasing hay storage capacity so that hay can be purchased when available, and pre-ordering hay in bulk from the same suppliers annually, can provide assurance for both producers and purchasers. This also reduces last minute sourcing struggles and ensures the best prices.

“We’re telling our horse customers that the way to make sure you have hay is to step up to the plate,” says Bland. “Tell us how much you need. Be professional and pay for it (preferably in advance). But at least have an order.” He also notes, “Smaller operators typically buy one or two bales at a time and if they stick to that they are going to be in big trouble.”

While many horse owners are simply trying to survive the difficulties of this year’s hay shortages, astute equestrians will be planning for future challenges. Advance planning and adaptation are key and can potentially reduce overall hay needs while ensuring sufficient hay in uncertain times.

Related: Wildfire! Flood! Earthquake!

Photo: iStock/BronwynB