By Lindsay Grice

Q I own a Quarter Horse mare I’ve bred and raised with the intent of developing a good show horse. She’s a beautiful mover and so far has placed very successfully in hunter flat classes, when she’s behaved. My goal is to show in other AQHA events such as equitation patterns and even Western pattern classes – horsemanship and trail. The problem is she can be quirky – quick to anticipate, easily surprised by a sudden movement of my leg or hand, even spray bottles can set her off. I can’t leave her tied because she’s been known to pull back when surprised. She takes some time to settle in with lunging and riding before she feels relaxed enough for the class. My instructor says I should just stick to the rail classes or else find a different horse. Am I wasting my time?

A You need to ask yourself how much time (or training money) you’re prepared to devote to turning your mare into an all-around horse. I’m big on being realistic about these things. We may hope for the War Horse story of taming and bonding with the volatile horse through perseverance, but in reality, such a horse is the product of both nature and nurture, and it takes a lot of work and skill to change that.

I’ve had several horses in my program that, despite their talent, were extremely frustrating in their early competitive years, similar to the mare you’re describing. After investing many years of consistent training they eventually desensitized to the situations that would formerly set them off. Now, as mature horses, they are successful, versatile competitors.

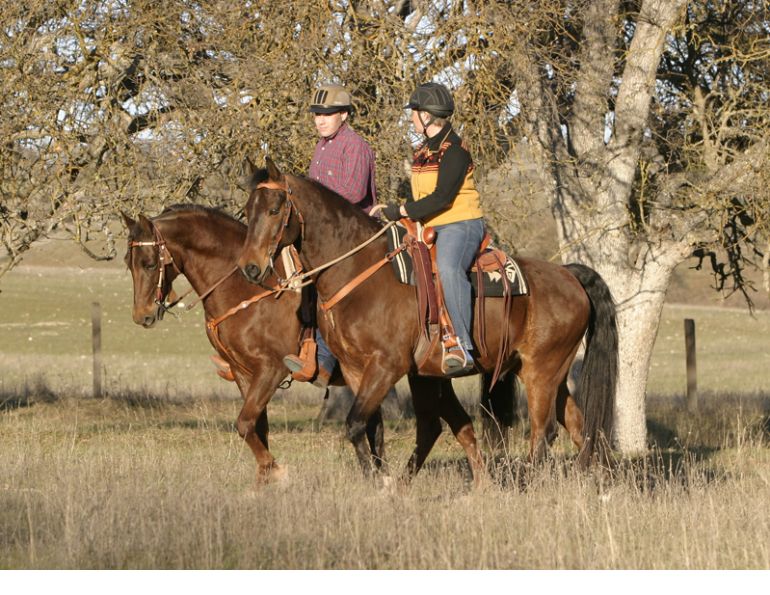

|

A competitive rider with a temperamental but talented horse might choose to make compromises such as avoiding tying or crossties. |

I have had other horses with quirks that we just decided to live with. I knew that tackling them head on would open up a can of worms which the owner did not have the time, motivation, or funds to deal with.

Changing behaviour is like creating a new pathway in place of a well-trodden one. It’s hard work and things often get worse before they get better. A competitive rider might elect to go with a talented but temperamental horse, knowing that compromises such as avoiding tying or crossties, not jumping, using scissors or tranquilizers for clipping and mane pulling, not showing in certain environments (i.e. coliseums, wet footing), or waiting to use the practice ring in the quiet, wee hours of the morning might be necessary. Though inconvenient, this rider might decide he could still accomplish most of his goals working with a high maintenance horse.

Habituation

If you’re bent on investing in your mare, you’ll need to habituate her to all her phobias and more. Habituation is the process of systematically desensitizing a horse to a stimulus by introducing it at a level that causes some stress but withdrawing it before it triggers her flight response. Let’s take a closer look at some of these key words.

Systematically – With any cue, I always start at level one on a scale of one to ten. For example, I don’t come right at the horse’s ear with the clippers, but start at the shoulder. I slide my leg back smoothly and slowly to ask for a canter transition rather than alarming the horse with a kick behind the girth. When the show arena is open for practice, I begin my warm-up by tuning up the controls (lateral work, transitions, small circles, etc.) in the centre of the ring before venturing toward the rail, grandstands, banners, and traffic flow.

|

Rhythm is important when it comes to desensitizing a horse. For example, if you’re introducing your horse to a trail gate, open and close the gate by only six inches rhythmically until he is indifferent to it. |

Use rhythm when introducing the stimulus. When introducing a horse to the trail gate, I might simply stand beside it with my hand on it. Then I’ll open and close the gate by only six inches beside my horse in a rhythm. I don’t change the rhythm until she is absolutely indifferent to it.

Western trainers use the term sacking out to describe exposure to something unfamiliar with a repetitive tempo.

Withdrawing – As with all training, you must make the decisions, not your horse. This requires that you make the decision to withdraw the stimulus before the horse withdraws from it.

When loading a hesitant horse onto the trailer, I make the decision to stop before she does. I may even back her up a few times before I ever ask her to put a foot in the trailer or on the ramp. I take my time. Withdraw the clippers before the horse decides to withdraw her head. Aim the hose first beside the horse, then away, then move it up just to the point of hesitancy, perhaps a hoof, then away, and so on.

Knowing when to withdraw requires good timing and the ability to read a horse.

|

Don’t let your horse bolt and buck on the lunge. This will only confirm your horse’s fear and teach him that it is acceptable to express a flight response in stressful situations. |

Flight – Horses, being prey rather than predators, have a flight response of “I’m outta here!” A prey animal rarely forgets something she learns through fleeing. If your horse flips her head out of your reach while you’re clipping her and finds there’s freedom there, she’s going to go there again. If she rears up and pulls away while you’re trying to load her in the trailer, she’s likely to try it again. If she kicks out at your leg in a canter transition and your leg comes off, she’s found her escape route.

Every time we let horses express their flight response by bucking on the lunge line, spooking to the centre of the arena, or tether-balling around us to avoid the spray bottle, we confirm their fear rather than habituate them to it. Allowing your horse to rush the approach to the jump and away again on the landing side confirms your horse’s fear that jumping is a scary process indeed.

You don’t want to trigger an adrenaline spike by moving up the scale too quickly. Don’t ask for anything that you may not be able to contain and don’t let the horse’s legs flee. Try to minimize the escape distance. This may involve sending the horse to “training camp” with a professional who specializes in breaking young horses thoroughly.

With time and consistency, almost every horse is able to get over the things that alarm her. Only you can answer the question: Is it worth it?

This article originally appeared in the October 2012 issue of Canadian Horse Journal.

Photo: Flickr/Sini Merikallio

Photo: Flickr/Sini Merikallio Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Ealdgyth

Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Ealdgyth