By Margaret Evans

Three hundred kilometres east of Halifax, Nova Scotia, lies a crescent-shaped island of sand 42 kilometres long by just 1.4 kilometres wide at low tide. Everything on this island – plants, animals, insects, the dunes themselves – is driven by the harsh influences of its foggy marine world where, over the centuries, this sliver of sand sculpted by churning seas and angry winds has been the graveyard of the Atlantic. Since 1583 there have been over 350 known shipwrecks on the island’s sand bars.

Sable Island (named Ile de Sable after the French word for “sand”) is the exposed part of a huge sand deposit on Sable Island Bank that formed during the melting of the last Ice Age. Fine sand was winnowed from melting glaciers and deposited in massive piles on bare land destined to be drowned as the sea level rose. Today the exposed arc of sand is driven, shifted, and re-deposited in a continuous-motion sand cell by tides and wind-whipped currents.

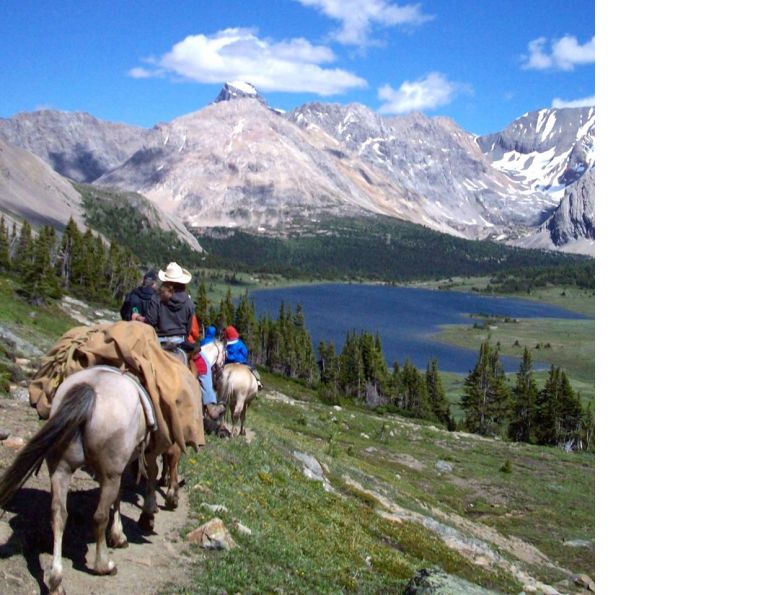

Young stallions on Sable Island form bachelor bands, mock-fighting and grazing together, and grooming one another. Photo courtesy of Zoe Lucas, Sable Island Green Horse Society

Everything on the island survives at the whim of the elements. The plants and the animals bind the fabric of the land into a cohesive whole, the most iconic being the marram grass which stabilizes the sand dunes by means of an elaborate root system and feeds the wild horses for which Sable Island is famous. Today, this unique sand dune world is Canada’s 43rd national park reserve.

The Sable Island landscape, with its shifting sand, salt spray, wind, and ground hugging plants and shrubs, is home to some 300 horses whose ancestors came to the island over 250 years ago. The horses’ story is tangled up in the conflicts and tensions between the Acadians and the British during the first half of the 18th century that finally saw the Acadians stripped of their land and livestock, and deported.

Acadians were the descendants of 17th century French colonists living in today’s Maritime provinces, then known as Acadia. They formed a distinct colony of New France and, despite the Conquest of Acadia in 1710 by the British, the Acadians consistently refused to sign an oath of allegiance to the ruling British authorities. So, between 1755 and 1763, approximately 11,500 Acadians were deported by the British to the New England colonies and France, leaving behind their possessions, including their horses.

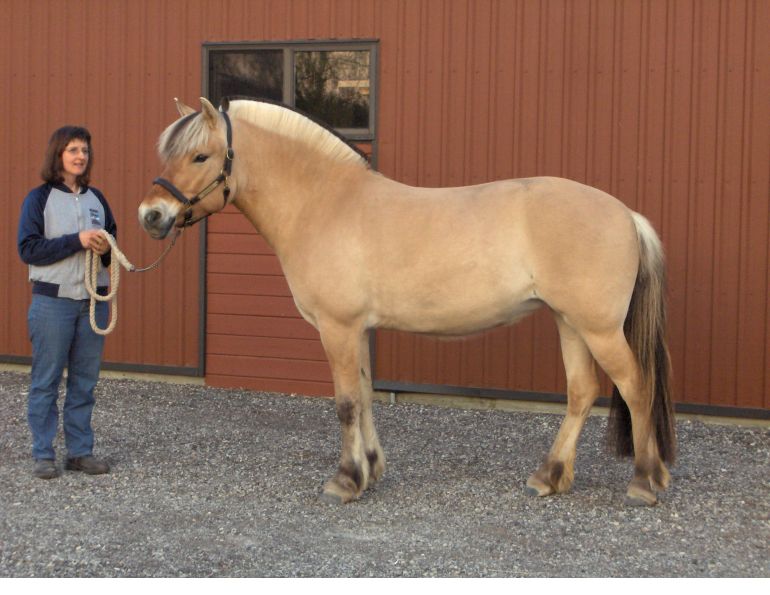

Sable Island horses have adapted to the harsh maritime environment by growing shaggy winter coats which they shed out in the summer and developing short pasterns that allow for easier travel over sand and rough ground. Photo courtesy of the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

Ship owner Thomas Hancock, who transported some of the Acadian people to English colonies, took 60 Acadian horses and shipped them to pasture on Sable Island where they were used to haul lifeboats and other equipment to save shipwrecked mariners. Despite the harsh conditions, the horses adapted and thrived. For almost 150 years, they were routinely rounded up and sold in Halifax, but in 1960 Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s government ruled that the horses be left on the island. Since then, the horses have been managed on a hands-off basis and in 2011 Sable Island became a national park.

The horses’ biggest issue, aside from extreme weather, is the abrasive sand. Grazing on the island’s plants, the horses consume a surprisingly large amount of sand and the gritty quartz particles wear down their teeth. Consequently, as they age they are unable to chew and properly digest vegetation. Since horses don’t replace their teeth, this can lead to death from starvation for older horses.

Their ability to adapt is testimony to the horses’ extraordinary survival skills. They grow heavy, shaggy coats with thick, long manes and tails to cope with winter elements, shedding out in spring to offset summer heat. Short pasterns let them travel more easily on sand and rough ground. Their typical colours are bay with some chestnut, palomino, and black.

Apart from extreme weather, the biggest environmental challenge faced by the Sable Island horses is the abrasive sand, which can wear down their teeth, leaving them unable to chew and properly digest vegetation. Photo: Flickr/Bernadette Morris

The sand dunes form ridges that give enough shelter to allow the island’s narrow interior to support ground-hugging grassland meadows, heath plants such as juniper, bayberry, crowberry, blueberry and cranberry, shrubs, and other vegetation. The dunes also keep ocean waves at bay, allowing fresh water from rain and snow to accumulate into ponds that are the horses’ water sources, both for drinking and as a means to cool off in summer heat. But in dry seasons, the horses have learned to dig for water to survive.

Sable Island horses express the same behaviours as many wild horses, with stallions owning harems. Foals are generally born in May and June. Young stallions form bachelor bands where they mock-fight, graze together, and groom one another. They move frequently from beach to sheltered ponds as the weather and grazing opportunities dictate.

Main photo courtesy of Zoe Lucas, Sable Island Green Horse Society