From Sahara to Atlantic

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

As we made our way up a searing gully of black boulders, I focused on pushing past the dryness in my throat and the sweat soaking my back. It was a late afternoon in February 2020, and I was leading Farouk, a spirited 18-year-old 14.1HH chestnut Arabian stallion, who was more inclined to gallop across the open desert than navigate the rocky ravines we now faced.

Our group consisted of 13 people: ten riders, a guide, an assistant guide, and a photographer, on an 875-kilometer expedition across Morocco. The journey began in the Sahara Desert in the east and would take us all the way to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. Our guide was well-acquainted with the first leg of the trip, but crossing the Anti-Atlas mountain range was uncharted territory for him. As we followed a barely used goat track and reached a cliffside with stunning views of the valley below, I thought to myself, "This might get tricky."

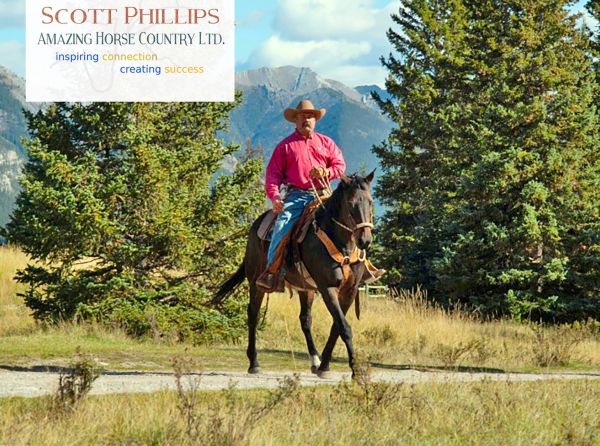

The horses were tough and fit, well-suited to the gruelling conditions in which they travelled up to 55 kilometres and 12 hours each day. The author and Farouk are shown in the foreground. Photo: Amanda Champert Photography

The author and her feisty mount, Farouk. Photo: Amanda Champert Photography

Riding across Morocco had never been on my bucket list. However, the previous mid-September, antsy that the Canadian trail riding season was winding down, I started looking for a long trip with faster riding in a warm climate. Ideally, the trip would be a relaxing holiday on a quiet horse that was happy covering substantial distance without too much rider input. When a four-week ride traversing Morocco came to my attention, I immediately contacted the organizer. After brief discussions, I was permitted to join the invitation-only trip. It was through an Islamic country I knew nothing about, whose language I didn’t speak, with a group of people I’d never met - a bit outside my comfort zone.

Fast-forward to late January, and I was one of ten riders and a photographer from Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, and the USA to arrive in sunny Marrakesh. We quickly bonded over culture shock and mutual loves of wanderlust and horses while driving for two days to a nondescript chunk of sand near Merzouga on the edge of the Sahara Desert. There, we were welcomed by our guide Abdel, introduced to a support crew of five easy-going Moroccans, and assigned horses. Nine horses were stallions while the other four were geldings, and they ranged from fine-boned Arabian types to stocky Barbs. I was assigned Farouk, a hot Arabian stallion with a lot of attitude, not what I wanted to ride for a month-long holiday.

Camels were a common sight along the route. Photo: Tania Millen

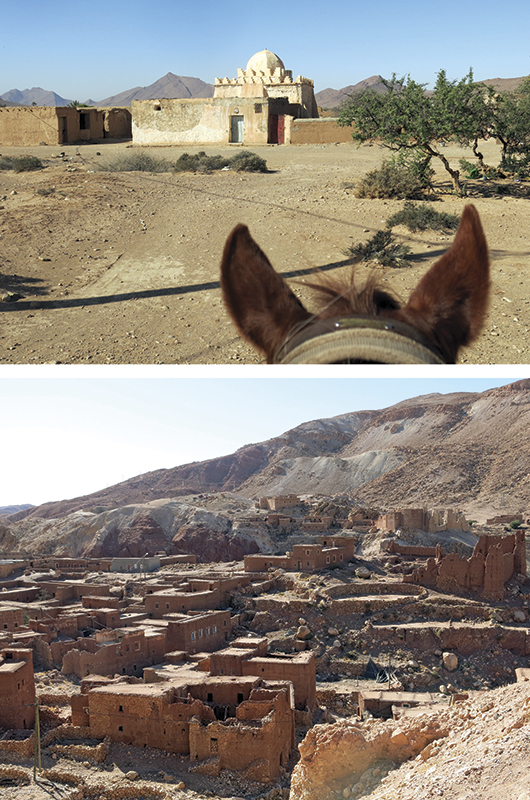

Traditional Moroccan homes were built for privacy and protection from the weather, with inward-facing rooms and windows, typically opening into a courtyard. The ride also passed by the ruins of a former village. Photos: Tania Millen

The expedition route had been scouted by our guide over the previous months and hadn’t been ridden in recent memory. We were traveling off roads and trails through remote, barren, desert, and mountains near the Algerian border. There was no suitable water or grazing, so all feed and water for horses and riders were supplied by a large five-tonne truck and Toyota pickup. Abdel and an assistant guide rode with us, while the cook and drivers met us for lunch. Then, while we rode across country, they drove indirect, difficult roads to set up our tent camp.

Related: Horse Packing Adventures in the Back Country

On the first day, knowing we had to ride over 40 kilometres per day to achieve our goal of reaching the sea 27 days hence, we adjusted our stirrups and hopped on our assigned horses, who promptly jigged, leaped, and bolted down the track. Farouk didn’t impress me. He cantered on the spot non-stop for 30 minutes before I decided to get off and hand walk. I didn’t appreciate his head-flinging antics or glare-squeal-strike routine when a horse got close, and I didn’t want to ride him. Nobody else did either. However, over the next few days, we came to a tolerable agreement: I rode him near the front of the group, stayed away from others, and gave him his own line for the gallops. He was a Ferrari among Hondas and represented his rugged ancestry well.

A beautiful oasis morning. Photo: Tania Millen

War forms the backbone of North African history. Europeans called the fearsome horseback warriors from North Africa “Berbers” — a derogatory Roman word meaning “barbarian.” Hence Barb (barbarian) horses were those the North Africans (Berber) rode. The origin of these tough, sturdy, enduring Barb horses over 1,500 years ago remains a mystery. In contrast, it’s recognized that Arabian horses were introduced to Morocco from Saudi Arabia in the seventh century. The Barb and Arabian breeds complemented each other. Arabians were lean, fast, and hot-blooded, while cooler-headed Barbs were sturdy and tough. Both were highly intelligent, sure-footed, had stamina and endurance, and thrived on meagre rations — all excellent traits for warfare and life in dry, mountainous country.

From the eighth century onwards, North Africans rode their horses into Europe to expand and defend their lands. These armies relied heavily on the courage and stamina of their horses, and the descendants of those tough, enduring horses exist today. Andalusian, Lusitano, Spanish Mustang, Argentinian Criollo, American Quarter Horse, and Appaloosa horses around the world contain Barb genetics, while an even greater number of horse breeds contain Arabian blood. The horses we were riding exemplified centuries-old genetics honed by Morocco’s endless conflicts and inhospitable landscape.

A room inside a former kasbah. Kasbahs are the walled citadels of many North African towns and cities where the ruling sheik or leader once lived. They are believed to have been used as watchtowers, with easily defensible positions and panoramic views. Photo: Tania Millen

Coming from Western Canada’s forested mountains and big rivers, the Moroccan landscape was difficult to comprehend. Up until about 5,000 years ago, the Sahara and its surroundings were more savannah than desert. Since then, the region has been drying up, and much of the area we rode through had temperatures averaging more than 40 degrees Celsius in summer with minimal rainfall. The vegetation was primarily small prickly bushes and thorny tamarisk trees. The land was composed of sand dunes, stony desert, rocky hills, flat former lake beds which made great galloping surfaces, and ancient cobble sea-beds where hand-walking was necessary. Massive riverbeds with six metre high embankments split the land, although rivers hadn’t flowed for decades or centuries. We followed the Dra’a River valley, which used to be the longest river in Morocco and flowed 1,200 kilometres to the sea, but is now dry. Sometimes it felt like we were riding on the moon, the land was so harsh. It was impossible to imagine how the few goats, camels, and nomads we saw managed to survive.

Related: On a Quest to Ride with Bison in Canada's National Parks

Our horses were impressive. We rode and hand-walked up to 55 kilometres and 12 hours per day. Water and feed were only available three times a day and the horses were staked on short ropes at night. Due to the rocky footing, we primarily rode at a walk with occasional trots, plus gallops up to three kilometres long. The horses had an unusual combination of endurance and sprinting fitness.

It was refreshing riding with a group of like-minded people who thrived on challenges and long rides. The riders became close-knit; we’d found our people. However, the cultural divide between the lives of us Western women riders and the lives of women in rural parts of Islamic Morocco was vast and difficult to fathom. They suffer from poverty and lack access to education and basic health care, and it was dispiriting to observe the struggles they face.

The nine stallions and four geldings on the ride were Arabians and Barbs, and they all had to get along. Photo: Tania Millen

After six days of riding and camping, we had a highly anticipated rest day in a riad (guest house) in the small town of Zagora, while the horses rested in camp. There were only three rest days on the 27-day journey, and they provided us with an opportunity to experience small-town culture, do laundry, and connect with family and friends online. Meanwhile, the Moroccan team shopped for food, fixed gear, and planned the next section of our route. Since we were traveling through remote areas close to the militarized Algerian border, we needed permission from every jurisdiction we passed through to traverse and camp in their area. Many evenings, officials would motorbike into camp to check up on us, collect passport numbers, and drink mint tea with our Moroccan team. Our guide was an incredible fixer who smoothed over problems as soon as they arose — a valuable asset for this logistically complex trip.

Riders and horses enjoy a restful lunch in an oasis. Photo: Tania Millen

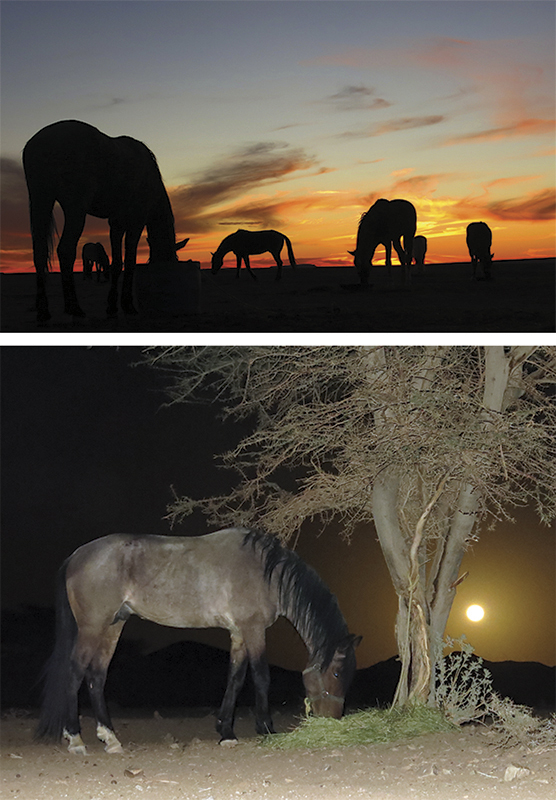

By the second week of the expedition, we’d settled into a daily routine of breakfast, packing up tents, tacking up, riding, lunch, more riding, setting up camp, and having a late dinner. And we all helped feed, water, and care for our loyal horses. Every day magnificent orange sunrises welcomed us as shadows and light played across the horses and landscape. As we roared across the desert, dust kicked up by the horses, wind-sculpted sand dunes, lone trees, ancient petroglyphs, lush small town oases, stunning pink sunsets, and the magic of a full moon all provided spectacular photographic opportunities. Becoming a superstar photographer overnight was an unexpected treat.

The horses carried their riders through narrow village streets, over sand dunes, and across wild and dramatic landscapes. Photos: Amanda Champert (top left) and Tania Miilen (top right, bottom left/right)

Another unanticipated delight was practicing Canadian grade-school French. Southern Morocco was a colony of France from 1912 to 1956 when the country gained independence from colonial powers, hence four languages are spoken there: Arabic, Berber, French, and a little English. Riding along trying to converse in rusty French provided many comical moments.

Meanwhile, I’d started appreciating Farouk for who he was and for carrying me across this unknown country. He hated being groomed — biting and kicking like a stallion possessed — so I groomed him immediately after riding before the sand and sweat dried onto him like a suit of armour. Massage went a long way, too, plus his favourite treat of dried bread became a saddlebag staple for the long afternoon rides. I also hand-walked a lot — sometimes up to 15 kilometres — which furthered our partnership and was a joy in itself. The deep snows of northern Canada’s winter don’t permit much walking, so it was wonderful to be able to stride along in the sunshine.

Hand-walking helped riders and horses connect. Photo: Tania Millen

The goat track ended on an escarpment in the Anti-Atlas mountains, with sweeping views. Photo: Amanda Champert Photography

Other than getting a bit lost in the Anti-Atlas mountains and topping out on that unexpected escarpment, where fortunately we’d found a very steep track down blocky boulders to the valley below, the expedition had generally gone as planned. By the third week, our goal of riding to the sea was within reach, and I was greatly anticipating galloping along the beach at Plage Blanche. Farouk was tired but fit and our partnership really shined at speed, so a beach gallop would be a fitting finale.

Related: The Lure of Horseback Adventure Races

Three days from the sea, refreshing fog from the coast covered the land every morning, saturating our tents and providing life-giving moisture to crops. In the afternoons, crazy winds from the Sahara hurtled sand at our backs, forcibly pushing us west. On our second-to-last day while hand-walking a tired Farouk, I stopped to take what would be my last photo of him, his ever-forward ears up, looking into the setting sun, seemingly keen for whatever would come next. But our luck was changing.

Top: The horses were fed and watered three times each day, and spent the nights staked on short ropes. Bottom: Massive dry riverbeds were common along the route. Photos: Tania Millen

A sandstorm arrived that night from the Sahara, flattening our tents and sandblasting the stoic horses. In the morning, a face-covering was mandatory to avoid inhaling sand and it was impossible to see without sunglasses. As we rode the last ten kilometres to the sea, visibility decreased to less than 30 metres; I could see Abdel in front of me but nothing else. It felt like riding in a vacuum cleaner. As we rode up a short rise, the wind almost blew Farouk off his feet and I squinted to see what was ahead. We were high up on an escarpment and as the wind eased slightly, I caught a glimpse of massive waves crashing onto Plage Blanche far below. We’d reached the sea!

Rocky hills and ravines often made hand-walking necessary. Photo: Tania Millen

Packing up on the last day in a fierce sandstorm. Photo: Tania Millen

Turning south, we rode along the cliff-edge, hunched over our horses, leaning into a wind so strong that small rocks rolled along the gravel track. Later we learned this sandstorm was so vast and ferocious that it forced closure of the Canary Islands airport located over 1,000 kilometres to the west. Eventually, a road led down to the beach, where the trucks and Moroccan team were waiting. After riding toward the sea it became obvious that it was unsafe to ride farther — there was water on two sides of us, no visibility, and the tide was rising. We hopped off our stalwart steeds, high-fived, and staggered back to the trucks to load the horses for their long drive home.

It was a fitting end to a challenging and rewarding ride, on a remarkable horse who, unexpectedly, stole a piece of my heart.

Check out more Holidays on Horseback.

Photo: Amanda Champert Photography