By Margaret Evans

In early 2010, the Governor of New Mexico announced that he would use stimulus funds to purchase 12,142 acres of land known as the Ortiz Mountain Ranch adjacent to Cerrillos Hills State Park and create a state-owned wild horse sanctuary.

While there are a number of environmental, economic, and public input hoops to jump through before horses are acquired, likely from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), now should be a perfect time to look at how these horses are going to be managed in the long-term to keep their numbers in check with the available range. It’s an issue that has as much relevance to the management of wild horse herds in Canada as in the USA.

The idea of individual sanctuaries has already been floated by US Interior Secretary Ken Salazar. In recognizing a growing conundrum with increasing herd sizes, overgrazed ranges, and a no-kill policy, he has taken a multi-pronged approach in encouraging the creation of wild horse sanctuaries in the mid-west and eastern states, the use of fertility control, and a more educational approach to showcasing free-ranging herds to a curious public.

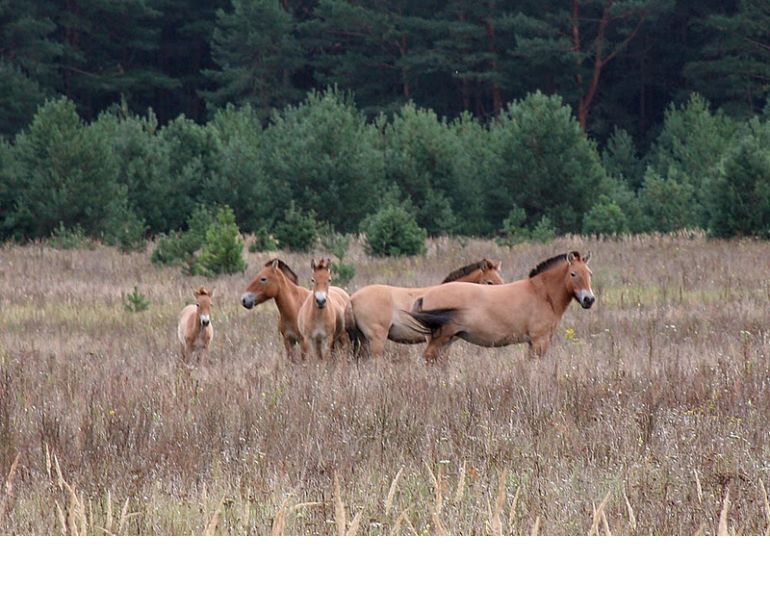

Wild horses across North America, from Sable and Assateague islands on the east coast, to the western plains of Canada and the USA, are an iconic feature of the landscape, representing not just their heritage but an evolutionary ancestry that began on this continent 50 million years ago.

Managing them today, though, requires some form of population control to keep numbers relative to resources and other wildlife communities. According to the BLM website, the free-roaming herd population of 38,400 animals exceeds by 12,000 the number that can be sustained on public lands in ten western states. Historically round ups, auction sales, and, in more recent years, adoptions have been the standard modus operandi of BLM. But with the recession there has been a sharp drop in adoptions or sales of eligible horses, leaving some 34,000 animals held off the range in corrals or controlled pastures at great expense to the taxpayer.

A better strategy for population control is needed.

In the past two decades, fertility control (immunocontraception) has proven to be arguably the most effective, the most humane, and the brightest long-term hope for wild horse herds.

“PZP (pig zona pellucida) fertility control in wild horses has been used successfully for 21 years,” said Dr. Jay Kirkpatrick, reproductive biologist and director of The Science and Conservation Center, ZooMontana, Billings, Montana.

Along with research colleagues, Kirkpatrick developed the fertility program in the late 1980s. When the National Parks Service (NPS) decided to manage wild horses on Assateaugue Island (ASIS) off the coastline of Maryland, they opted for a mechanism that was “humane, effective, and publicly acceptable” to the two million visitors who enjoy the horses every year.

“They chose the fertility control route and we did the preliminary research from 1988 to 1993 to establish safety and effectiveness,” explained Kirkpatrick. “Then in 1994 the NPS began actual management of the herd with PZP. Their first goal was to stop growth in the herd which, at that time, was 175 animals. We did that almost immediately. The second goal was to bring the herd to 150 using only contraception and we did that by somewhere around 2005. The third goal was to bring the herd to approximately 100 and we are currently at 116, all without the removal of a single animal.”

PZP, an immunocontraceptive administered by a dart gun, has been used to manage the wild horse population of Assateague Island in control since 1994. The goal of using PZP on the Assateague horses is to maintain a genetically sound population of horses within a safe margin. So far, the program has brought the herd from 175 to 116 animals using only contraception. Photo: Courtesy of The Science and Conservation Center, ZooMontana

PZP is a vaccine made from a protein in pig oocytes (eggs). It stimulates a mare’s immune system to produce antibodies that prevent a stallion’s sperm fertilizing her egg. The vaccine is administered with a dart gun and, given in spring, does not interfere with a current pregnancy. It has been shown to have no side effects, does not impact a band’s complex social behaviour, and can be maintained each year with a booster. It is also reversible, to bring the mare back into fertility.

The ongoing work has been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and over the years every aspect of the herd — population changes, safety, genetics, behaviour, and reversibility — has become the most extensive and innovative process Kirkpatrick has seen in nearly 40 years in wildlife management and reproduction work. The core science was aimed at maintaining a genetically sound population at a level well within the safe margin of a minimum viable population (MVP) which, for Assateague, is 48 animals.

The success of immunocontraception as a management tool in both captive and free-ranging wildlife species is widespread. Fertility control is used on African elephants, urban deer, Catalina Island bison, Asian macaques, and in a host of zoo populations around the world. While the Assateague Island horses became the flagship herd back in the early 1990s, the management technique is in play in a wide number of herds across the western states. It is now being applied to the acclaimed Pryor Mountain herd which ranges in 31,000 protected acres along the Montana-Wyoming border where they have a similar history and structure to the Assateague horses.

According to Kirkpatrick, both herds are historic. The Assateague horses arrived on the island 350 years ago and the Pryor horses have been established for at least 200 years. Both have a legal mandate for their existence. They have similar population variables ranging from 100 to 200 animals and both pose a threat to their environment, one being a fragile barrier island and the other being a drought-ravaged upper Sonoran desert.

PZP works by causing a mare’s immune system to stop a stallion’s sperm from fertilizing her egg. It is effective, humane, has no side-effects, does not impact the herd’s social structure, and is reversible. Photo: Courtesy of The Science and Conservation Center, ZooMontana

“Gathers and removals of Pryor horses have been going on since the range’s establishment in 1968,” explained Kirkpatrick. “Because it (a gather) does not attack the fundamental problem, i.e. reproduction, the herd simply increases after each gather and the process goes on ad infinitum. In contrast, the NPS attacked the problem (at the source). The ASIS herd was stabilized and is heading for the goal of 100 animals without the removal of animals or the disruption of social groups and behaviours. The secondary effects of the ASIS fertility control management have been a three times increase in longevity for mares, decreased mortality, and increased body condition scores. None of that has happened with (horses subjected to) gathers and removals.”

In 2009, BLM conducted not only a gather and removal of Pryor horses but also introduced a long-acting form of the fertility vaccine to 39 mares. The round up, though, proved to be extremely unpopular given stress factors, potential for injuries, the break-up of family bands, and the dispersal of young stock which removed future genes from the herd.

Currently the BLM is working on an environmental assessment which might, in the future, follow the ASIS plan. Some 17 Pryor mares were treated in spring 2010. Once the new assessment has been completed, Kirkpatrick is hopeful that many more mares will be treated with the PZP vaccine in the coming years.

In an economic time when budgets are tight, cost and time effective management strategies are absolutely essential. The success of the PZP program has gained worldwide attention and enquiries continue to be received from diverse management groups looking to start similar fertility projects to control such populations as New Forest and Dartmoor ponies in the UK and Przewalski’s horses in Hungary.

In the BC Interior, the non-profit organization Critteraid has taken the initiative with their “Project Equus” to offer some unique options to the Penticton Indian Band to help in the management and population control of their free-ranging horses, where animals in poor condition continue to breed on overgrazed land. In addition to offering a program that addresses public safety, sound equine health, sustainable range management, and compassionate training, they are proposing fertility control for approximately 200 horses. Critteraid has already underwritten the cost for one individual to receive training from Kirkpatrick in the use of the dart gun and administration of the vaccine.

One shot at a time, wild horses are benefitting from a non-invasive, humane, and controllable way of keeping their populations in check while their ancestral ranges are managed in sensitive and sustainable ways.

Main photo: Claudia Notzke, Associate Professor, Faculty of Management, University of Lethbridge - Immunocontraception has just begun being applied to other groups of wild horses. This black stallion and his mare are from the Pryor Mountain National Wild Horse Range, located on the Montana-Wyoming border.