Four Symposiums Across Canada

By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

“Riding is a lifelong learning process,” says Christoph Hess, a retired FEI 4* dressage judge and Level 3 eventing judge. “After riding one horse, you might think you’re a hero, but then you ride another and wonder whether you can ride at all.”

That was just one nugget that Hess shared with over 40 Canadian riders and approximately 800 spectators at four two-day symposiums in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Prince Edward Island in May 2023.

“Fasten your seatbelts; Hess is a firecracker,” said Leanne Binetruy when introducing the classical dressage maestro in Blackfalds, Alberta on behalf of the Western Canadian Dressage Symposium organization.

Riders representing all levels and abilities — FEI Children’s, Young Riders, U25, adult amateurs, para-equestrians and professionals — rode green three-year-olds to late-teen grand prix horses. Some of Canada’s top dressage riders participated including Carmie Flaherty, Claire Robinson, Colleen Church McDowell, Jacqueline Brooks, Jamie Irwin, Maya Markowski, and Pia Virginia Fortmüller. Other icons of Canada’s dressage community audited.

“It’s an honour to teach these symposiums,” said Hess. “Not just to explain how to ride better or present the horse better in a test but to explain the horse’s point of view.”

Hess has been involved with the German Equestrian Federation and German Olympic Committee for almost 40 years and is a highly regarded coach worldwide. He judged five- and six-year-old dressage classes for 20 years and is deeply committed to the classical principles of correct training.

The writer attended the symposium on May 6, 2023 at Horse in Hand Ranch in Blackfalds, during which Hess emphasized the importance of doing what’s best for horses. He consistently focussed on basic principles, while encouraging riders to work harmoniously with their horses and maintain a correct position.

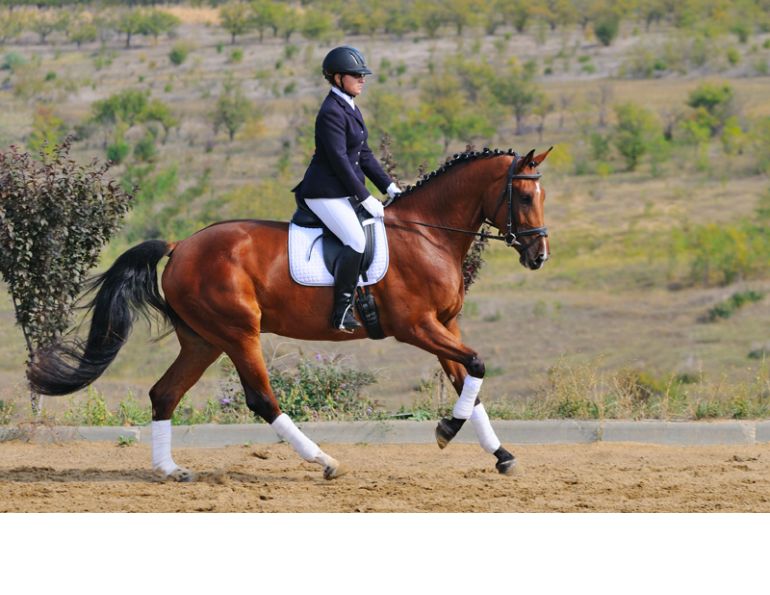

Above: Pia Virginia Fortmuller riding Calisto, her mother’s homebred four-year-old CSHA gelding by Casparo out of a mare by Christ. Fortmuller and Calisto work on engaging the inside hind leg by doing shoulder-in. Calisto has been started over fences as well as on the flat and may event this summer. Fortmuller is based in Priddis, Alberta. Photo: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

Above: Jenneke Hoogendoorn shares information about Hampton, her 2012 KWPN gelding by Rousseau out of a Flemmingh mare. Hoogendoorn operates an equestrian centre in Stoney Plain, Alberta and has brought Hampton up through the levels herself. She plans to show Prix St Georges this year.

Photos: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

Below: Hoogendoorn and Hampton warm up prior to riding ten lines of flying changes.

“We have to train the horse to use its body in a biomechanically correct way so that it’s mentally and physically relaxed and supple and able to do the work,” says Hess. “From an ethical point of view, it’s our responsibility to consider what the horse is capable of and not ask for more than that.”

Hess began every lesson asking the rider to share their horse’s history and what their goals are. Then the rider did a short warm-up, was assessed by Hess and the spectators, and shared how they felt the horse was going. Regardless of the horse’s level — from young horses to well-established grand prix horses — Hess focussed on how to help the horse do what was required while understanding their needs.

Related: Grooming Horses at the Top

“Balance is one of the most important things,” says Hess. “Horses use their neck to balance their body in dressage, show jumping, and cross-country. The whole discussion about short necks is wrong. Low, deep, and round? Forget it. I’m happy that we’re now judging and training in a horse-friendly way, with an open throat latch that allows the horse to balance itself. In the old days, I think most judges didn’t know how bad it was to ride the horse with a short neck.”

“There are many brilliant horses around the world that are too ‘easy’ in the contact — they’re not stretching into it,” says Hess. “We need to stretch the horse’s neck and open the throat latch so that the horse can use its whole body to balance.”

Hess also emphasized rider balance.

“Good riding starts with a well-balanced position,” says Hess. “If you don’t have a good position in the saddle, then your riding will be weak. Whenever we use the reins [for balance] we’re working against the horse and it will feel unhappy. Then the horse will run away [push into pressure], curl up, get tense, or other things. Too many riders use the reins to find their balance in the saddle.”

Related: Respect from Your Horse Starts Here!

Leanne Binetruy riding Shooting Star, a 2010 Oldenburg gelding by Hit Parade. Binetruy encourages Star to lengthen his frame and telescope his neck while maintaining rhythm. An adult amateur, Binetruy plans to compete Prix St Georges this summer and was part of the organizing committee for the Alberta symposium. Photo: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

Hess also emphasized rising trot rather than sitting, so the horse can use its body.

“Rising trot helps you get into better balance,” says Hess. “In Germany we call rising trot ‘easy trot’ — it’s easier for the horse. We need to do things in a way that makes the horse more comfortable.”

Hess encouraged many riders to canter in two-point position to encourage free movement and relaxation in their horses.

“Two-point seat is like a piece of sugar for the horse,” says Hess. “It’s useful for riders to find their balance, especially for amateurs who sit in an office in front of the computer all day.”

U25 rider Claire Robinson rode her challenging but talented 2015 KWPN mare Kappuccino TC, by Desperado NOP out of a Wolkentanz II mare. She was tasked with cantering Kappuccino TC one-handed while encouraging relaxation. Photo: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

“When you have a problem, don’t fight with the horse or force it,” he says. “Ask yourself whether the horse understands. Think about how to have better communication with your horse. Cooperation and harmony are key.”

“We have to point the finger at ourselves,” says Hess, “and not say My horse has to be better at this, that, or the next thing. We have to ask ourselves What can I do better? How can I have a better position, better balance, more relaxation? What can I do so that my horse will understand my communication?”

“Riders need to reflect on what they’re doing,” says Hess. “That’s how you jump up the levels. You can’t just look for answers from your coach.”

Riders were encouraged to garner more impulsion and consistent contact through transitions, going forward, longer reins, and two-point position.

“Grand prix is basics, basics, basics,” Hess says. “Get the paces and basics correct on circles, then move on to specific movements.”

For example, he suggested using shoulder-fore to get more bend and the horse sitting on its hind end, using corners to create more suppleness, then moving on to half pass.

Related: Riding Horses After Sixty

Cheryl Roberts riding her 2010 KWPN gelding Famous Forever, asking him to stretch forward into the contact, creating a lovely picture. Roberts and Famous Forever compete at Prix St Georges and Intermediate I. Photo: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

“The best exercise to control the tempo is shoulder-fore or shoulder-in,” he says.

Hess suggested canter-trot transitions to maintain a forward tendency and keep the horse in front of the rider.

“Think about starting the trot from the canter, not falling into it,” says Hess. “From trot to walk, you start the walk. We have to school this from the very first day.”

He encouraged several riders to canter on a longer rein to encourage the horse to stretch into the contact.

“We are working on collection when we go forward with long and loose reins,” says Hess. “You can’t collect a horse that isn’t moving by themselves.”

“Loose rein [at the buckle] is very important for developing confidence between the horse and rider,” says Hess. “Our horses must be able to maintain balance, rhythm, and tempo with a short rein, long rein, and loose rein.”

Those working on flying changes got this advice.

“Ninety-nine percent of the flying change is preparation,” says Hess. “Control the canter between the flying changes with your legs and body, not the reins.

“When training, don’t ask for a flying change when there is tension or the tempo is out of control,” Hess says. “And don’t count. Ask when you have a good feeling. Better to start the changes across the diagonal too late, but when the tempo is in control, than too early.”

Hess had the riders take short breaks to allow their horses to relax, and to share what they were feeling with the audience.

During her ride, Binetruy shared, “Continuously giving the reins prevented me from locking on and pulling. I loved it. He was soft and more forward.”

After working on flying changes, Jenneke Hoogendoorn said, “My horse knows what to do, he just needs me to get out of his way.”

Hess also shared tips about navigating competitions, saying his marks start at 10 and drop from there.

Related: Peter Gray Dressage Symposium

“Good riding begins with straight long sides and going into the corners,” he says. To get high marks with an “ordinary-moving” horse, he suggested riding each corner as part of a six- to eight-metre volte (circle) and preparing for the next movements on the short side. “Use the corners to bend and flex the horse, to get it to use the hind leg.”

If the horse is “looky,” he said to go forward to inspire confidence. And don’t worry about making mistakes.

Above: Annie Coward with her KWPN mare Diolita DN, by Tango out of a Glendale mare. Coward came up through the Young Rider ranks and is now competing U25 Grand Prix.

Photos: Nicole Marie Photography Co.

Below: Coward and Diolita work on their flying changes.

“Horse and rider combinations that are trained correctly make mistakes, but only a single mistake,” says Hess. “They don’t multiply or create a domino reaction. Plus, when the training is correct and communication is clear, it should be easy to correct mistakes.”

Hess complimented all the riders at the Alberta symposium, but Claire Robinson, a U25 rider, and her mare Kappucino TC, stood out.

“This is a top horse and rider combination heading for the international arena,” says Hess. “Not all horses have the talent for grand prix — they need more spirit and more petrol in the tank than other horses. The more talented they are, the more time, passion, and patience they need. This horse is difficult to ride. It’s a Ferrari. It’s a really special horse.”

Robinson admitted she was nervous before her ride but excited to get another perspective. “It’s all fundamental basics — rhythm, relaxation, contact,” Robinson says. “They’re universal, right?”

Hess challenged Robinson to reduce her mare’s tension by riding one-handed at canter, giving the reins, and controlling the horse with her position.

Related: Finding Paths to Success for Equestrian Youth

“This is how you have to train horses with a lot of talent like this one,” says Hess. “She’s doing a great job.”

Hess’s teachings were well-received, and many riders made substantial changes.

“Hess is a legend,” says Hoogendoorn. “I have a major hiccup on the changes, and he made me do about ten lines of them. It was great to just relax in the ring and think my way through things instead of reacting. To feel like You can do this; you’ve got it.”

Attendees across the country indicated the symposiums were inspiring and educational.

“It’s awesome what the organizers put together and how they treated everyone,” says Hoogendoorn.

Those sentiments were reflected by many, who hope that Hess’s guidance will reverberate through Canada’s dressage community for months to come.

Related: The Madden Method Symposium

Related: Becoming a Horseman: What Does It Mean Today?

Main photo: Christoph Hess with Jenneke Hoogendoorn riding Hampton. Credit: Nicole Marie Photography Co.