By Margaret Evans

It is common knowledge that a horse must achieve optimal physical fitness in order to deliver a peak performance, but what kind of impact does psychological condition have on equine performance? In a competition environment, equine athletes in any discipline may show symptoms of stress, but to what degree does the expression of that stress affect the quality of a jumping round, dressage test, reining pattern, etc.? And how great is the rider’s ability to influence, either positively or negatively, the horse’s psychological state?

Recent years have seen these questions become the focus of a growing number of studies on the psychology of performance horses, several of which have yielded interesting and applicable results.

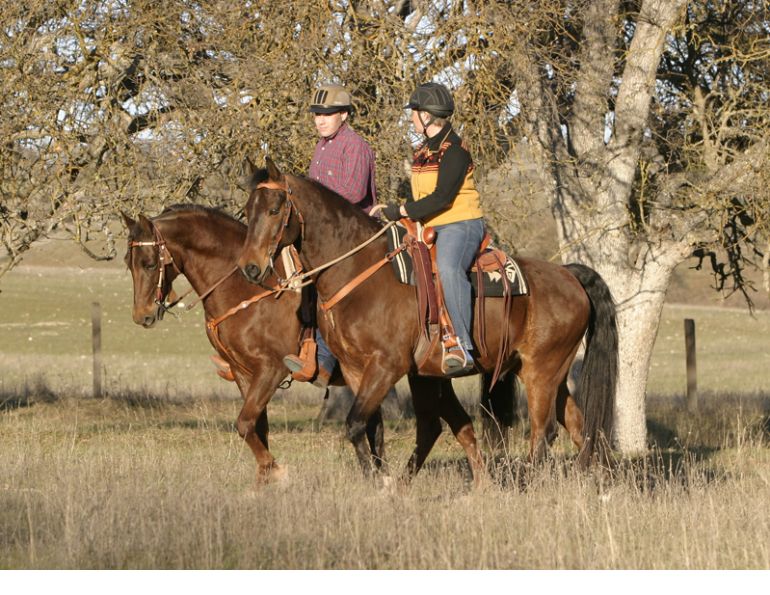

Just as a Shetland Pony will never win the Kentucky Derby, so a horse with an inappropriate temperament for a particular discipline will typically never excel in that discipline. Photo: Sara Graham/Flickr

In the paper entitled “Psychological Factors Affecting Equine Performance,” published in September 2012 in BMC Veterinary Research, British researchers Dr. Sebastian McBride from the Royal Agricultural College, and Prof. Daniel S. Mills from the University of Lincoln, review the current research and confirm that the horse’s temperament, mood, and emotional reaction play a significant role in determining equine performance in a competition environment. The authors state that “Psychological factors exist at three interrelated but separate levels: temperament, mood, and emotional reaction. Temperament exists as a relatively stable predisposition in adult life which is shaped by genotype and early experience, whilst mood describes a more temporary state of psychological functioning which helps to bias behavioural choices toward certain types of action in a predisposing environment. Emotional reactions are the most tightly stimulus-bound affective states and the shortest lived, thus describing the more immediate response to the subjective evaluation of an event.”

Like physical traits, an individual’s psychological characteristics, including temperament, are a product of the interaction between the expression of that individual’s collection of genes, or genotype, and the influence of environmental factors.

McBride and Mills describe the optimal genotype for a horse, with respect to both physical and psychological traits, as being discipline specific: “Just as a Shetland will never win the [Kentucky] Derby, so a horse of inappropriate temperament will generally never succeed within a certain discipline. It is therefore essential, not only to concisely define the biological basis of temperament, but also to identify very carefully which components (at the level of both specific behaviours and behavioural predispositions) are required to achieve success within a given discipline.”

A better understanding of temperament could result in the development of temperament tests that would enable us to accurately predict a young horse’s future potential in a given discipline. Photo: Carine06/Flickr

For example, Thoroughbreds as a breed may often be described as flighty, while Quarter Horses on the whole might be labeled as quiet. But flightiness can be considered a desirable personality trait in a racehorse, where it would be certainly be regarded as a flaw in a reining or cutting horse.

Identifying the specific traits that are sought after within different disciplines is important in the development of objective criteria for evaluating equine temperament as a predictor of future performance, and could prove to be a useful tool for creating effective training regimens.

“There is continual work in the area of establishing early behavioural markers for future performance and also quite a lot of work investigating different training strategies in terms of optimal learning that keeps stress levels to a minimum,” says McBride.

The research report adds that temperament testing is often only useful for practical purposes if it is predictive of how an animal reacts to a range of situations over time. Some studies have shown that while individual animals are consistent in their response to different tests, consistency over time is more difficult to assess.

Understanding the temperament of a young horse and then being able to accurately assess its future potential in performance would provide a huge advantage for riders planning to invest considerable time and money in conditioning and training. But as McBride and Mills point out, “much more validation-type research measuring a full range of concisely-defined early temperament traits for the purpose of subsequent correlation with discipline-specific performance is required.”

While temperament is greatly impacted by genetics, other factors affecting equine performance may be more dependent upon external factors.

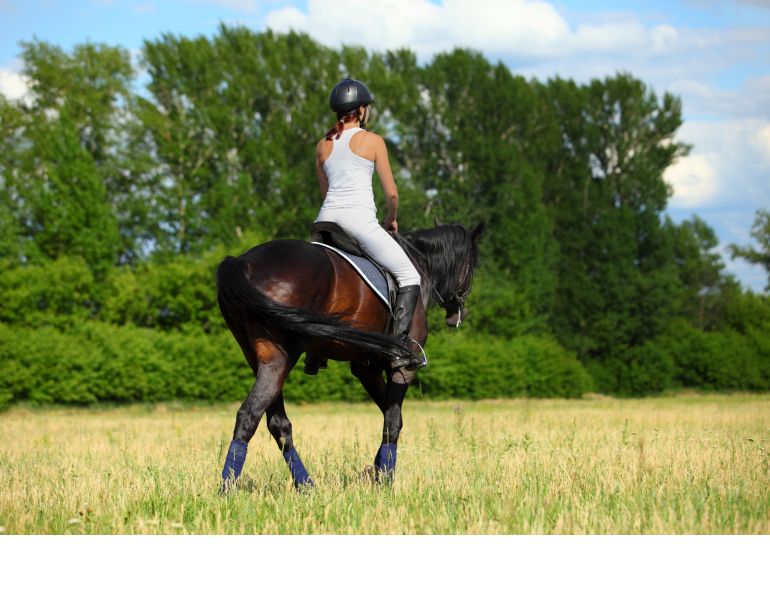

A horse’s mood and emotional reaction are in large part shaped by any number of stressors in a given environmental situation, and play a significant role in determining how he experiences and responds to that environment, which, by extension, impacts his performance. However, it seems that an experienced rider can, using superbly timed training aids, have a considerable influence on the horse’s mood and emotional reaction.

“Ultimately, high performance riders that are doing well are intuitively and consistently making these sorts of judgments correctly about their horses,” says McBride. “Nonetheless, we often see it go wrong at the point of competition, i.e. refuse jumps, run out, don’t respond, which means that there might be ways of pre-empting ‘off-days’ by monitoring mood and emotion in more consistent and standardized ways. The studies done on mood and emotion have predominantly used inferred measures of optimism and pessimism.”

If a horse’s mood is negative, then in all probability his emotional reaction to a given situation will be negative, which is likely to result in poor performance. McBride and Mills point out that mood assessment before competition could potentially be a useful predictor of poor performance, but that more extensive research in this area is needed before standardized assessment techniques can be established.

Our comprehension of equine mood and emotional reaction, while critical to understanding how a horse perceives and reacts to his environment, can be elusive. There is still a greater need to understand the effects of the rider’s emotional state on the horse.

According to McBride and Mills, “Horses are known to react differently when stroked by someone with a negative attitude to them compared with a more positive attitude, and so they may detect changes in rider behaviour due to such things as competition anxiety.”

However, another study, conducted by a research team from the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria, in collaboration with the Ecole Nationale d’Equitation in Saumur, France, indicates that a rider’s emotions might not have such a great impact on the horse’s performance. This study consisted of measuring the changes in various stress-related parameters, including stress hormone levels in saliva and regularity of pulse rate, in both the horses and their riders in a specific competition. Measurements were taken first during the warm-up away from spectators, and then again during the actual performance in front of an audience of one thousand people.

According to the research report, entitled “Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: Different responses to training and performance,” which was published in the February 2013 issue of The Veterinary Journal, the initial results of the measurements were congruent with what the researchers had anticipated. Symptoms of stress – higher cortisol concentrations in the saliva and a more irregular heartbeat – were recorded in both the horses and their riders, with riders showing significantly higher levels of stress when performing in front of an audience. No surprise there. Even experienced riders get stage fright.

The horses, however, were unaffected by the presence of spectators. Their reaction to the course they had to navigate was independent of whether an audience was there. These results came as a surprise to the research team, because they implied that riders do not communicate their heightened anxiety to their horses. This lack of transfer of emotions between rider and horse was completely unexpected.

“We started with the assumption that the rider’s stress would affect his horse but this does not seem to be the case,” said Christine Aurich at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna. “Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that we were working with experienced horses and highly skilled riders. Our findings cannot be generalized to inexperienced riders who might be less able to prevent their horses from being stressed by the situation.”

Research into performance horse psychology, particularly with regard to the interrelationship of horse and rider emotions, is clearly a work in progress. Undoubtedly, the future results of those studies will be of great benefit to riders and their horses. For time being, it is safe to say that today’s level of competition and performance in the world of equestrian sport puts great expectations on each horse and rider pair. A performance horse’s physical and psychological traits should be taken into consideration when predicting his success in a given discipline, and when designing a training regimen for him that includes mechanisms for reducing overemotional reactions on competition day and for coping with any negative experiences that might arise and influence an emotional response.

Main photo: Oliver Abels/Wikimedia Commons - An experienced rider may be able to influence a horse’s mood and emotional reaction so that the horse can be coaxed through a stressful experience.