By Lindsay Grice

Q: I’m an amateur rider who does most of my own training, and supplement it with the occasional lesson and clinic. While the technical skills I’ve been learning from the professionals have been helpful, I’d like to know more about the bigger picture. For example, why do these skills work? I’ve heard you talk about the importance of thinking like a horse when riding, and I hope you can give me some insights…

A: Without a doubt, an awareness of the way horses learn has helped me to train more efficiently, effectively, and safely. Like a detective, I approach issues by asking the question, “Why might this be happening?” I look for clues and go through my mental Rolodex of equine behaviour facts to solve the puzzle. Problems occur when we try to fit the square peg of horse thinking into the round hole of people thinking. Anthropomorphism, or attributing human qualities to our horses, can get us into trouble. Horses and humans are wired very differently. Effective trainers understand how horses perceive the world, what motivates them, and how they learn.

Here are some things to keep in mind...

Horses are herd and social animals.

Horses find comfort and safety within a herd. The alpha horse, or leader, is the one who makes the decisions about when to seek out water, shelter, or rest, and the subordinates trust and follow. As horse trainers, humans must be the leaders. We call the shots, such as exactly which path we are going to travel, where and how long we are going to stand still, and the pace at which we’ll move. This takes a lot of energy and planning on our part because whether we’re aware of it or not, from the moment we walk the horse out of the stall, we have either assumed leadership, or we’ve transferred the decision making status to the horse. As the decision maker, we need to have a lesson plan for handling the horse in the barn aisle, leading him to the paddock, mounting, and riding in the arena.

Alpha horses confirm their dominance by their ability to use threatening body language to cause their subordinates to retreat. No horse has permission to step into the leader’s personal space uninvited. Body language is the major way horses communicate, and a good horseman will do the same. As a regular exercise and throughout the training process, the handler should ask the horse to step away from him (either backwards or to the side) and to yield to pressure applied to any part of his body. Handlers who step back when longeing, or in the barn aisle, may be unaware that they are inviting the horse to step right into that leadership vacuum and possibly barge right into them. Always be aware that you are training. Inconsistency, such as being cuddly and permissive on one occasion, and slapping and jerking the horse on another, will confuse him. Nothing is more baffling to a horse than boundaries that change.

Horses are prey animals, humans are predators.

Prey animals need to be more wary than predators in order to survive. When they perceive frightening stimuli, they flee, and they don’t stop to ask questions. This fright-flight response is the source of the instant reaction time we experience as riders trying to stay on board during a spook. As the alpha, we can train horses to trust us in the presence of something spooky, and override the flight response. Through repetition, we can desensitize horses to spooky objects.

Horses are herd animals and find comfort and safety within a group.

Riders are often quick to lose patience with the horse that spooks at imaginary ghosts, but the horse, in fact, perceives far more than we are aware of. Programmed to constantly be on the lookout for danger, horses are quicker to detect stimuli than humans. They have a wide field of vision because their eyes are situated on the sides of their heads, as opposed to humans with binocular vision. Although they have a limited view of things directly in front, by turning their heads slightly, they can view most of what lurks to the side and behind them. In addition, horses can hear a wider range of sounds than humans, and, with ears that swivel around like radar, they can localize the source of that sound.

If a horse is trapped, and cannot find a way to flee from what’s frightening him, he’ll often fight. Picture a horse pulling back when tied, or having his leg tangled in a fence. In training, we must always provide a way out, or an open door. If, for example, we ask the horse to bend with our inside rein, our outside rein needs to give. Freedom is a reward. In the words of the well-known horse trainer, Ray Hunt, “make the wrong thing difficult and the right thing easy.”

The trainer should avoid creating fright. Emotions and adrenaline do not foster learning. The emotional horse is bent on fleeing scary situations. In flight mode, his movements become quick and unnatural instead of long, soft, and calm. The only possible training benefit of creating fear would be when a horse has exhibited truly aggressive behaviour such as striking or biting. The trainer must assert his leadership, followed by an instant reward when the horse responds positively. It is crucial for horsemen to be in control of their emotions, and of the timing and intensity of their cues.

Horses learn differently than humans.

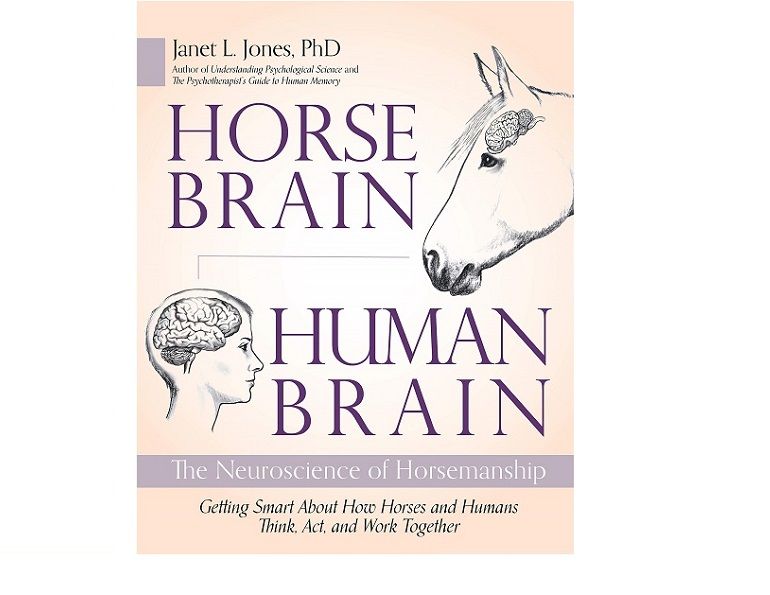

I’m often asked if humans are smarter than horses. Although the horse has a far smaller brain size to body size ratio than a human (the equine brain is about the size of a grapefruit), this is really like comparing apples to oranges. It’s less about size, and more about structure and the motivation to learn new things.

Horses’ brains are structured differently than humans and this explains some of the frustration we may encounter when we try to use human logic in training. Scientists tell us that the neocortex, the centre required for higher mental abilities, (i.e. reasoning, abstract thinking, logic) is larger and more developed in the human than in the horse. These are crucial mental functions for the predator that uses strategy to track his prey and predict its movements.

In contrast, the horse’s brain is dedicated to tasks relating to survival, i.e. physical sensitivity and locomotion. As a prey animal, the horse is up and running soon after birth, sorting out the information he picks up from the environment with his keen senses. He’s motivated to eat grass all day and flee danger. Problem solving is not a necessary skill, hence he learns through experience. We can’t count on a horse to reason through a skill that we’re teaching him, or imagine the outcomes of performing it correctly or incorrectly. He learns through trial and error which requires patient repetition on our part until he understands what is being asked of him.

So the next time you’re tempted to anthropomorphize, remember that horses and humans are wired differently, and try thinking like a horse instead!

Main article photo: A horse’s brain is dedicated to tasks relating to survival. The horse does not possess or require the higher mental abilities of reasoning, abstract thinking, and logic.

This article originally appeared in the October 2011 issue of Canadian Horse Journal.