This article was published in 2018. Some of its details may be outdated.

Retraining the Off-The-Track Thoroughbred

By Margaret Evans

When our Thoroughbred mare, Daisy, returned home after the racing season, she was fit, lean, and highly wired.

Three-year-old Daisy had done relatively well at Hastings Racecourse in Vancouver, BC. She had won her first race that season, and had placed in many others. When she came home that fall, we decided to breed her. She would have some downtime before going off to the stud farm in early spring. But over the winter, I realized our smart, high-strung filly would need some retraining to reinforce basic manners not only for safe handling, but for her future as a pleasure riding horse.

Daisy was a fidget. She couldn’t be left in the barn alone even for a moment, wouldn’t stand still for grooming, and was fussy about having her feet picked up even though she had been shod regularly at the track. Physically she was healthy with all shots and dewormers up to date, but what she needed was a more relaxed frame of mind.

Thoroughbred horses are legendary in their ability to leave the racetrack environment and go on to brilliant new careers in competition such as hunter/jumper, eventing, dressage, flat and hack shows, Western disciplines, or become working ranch horses or pleasure mounts. But they come from the track with their own unique set of experiences and habits and must frequently be reprogrammed with a new, focused mindset.

Every year a steady stream of horses find themselves at the end of their racing careers for various reasons. Some have an unsoundness, which must be addressed before retraining can begin. Many issues can be overcome with rest and rehabilitation, and a vet check should be done to determine if the horses is sound and to identify issues that can be managed. Photo: ©Canstockphoto/Kiankhoon

Understanding these habits and having a game plan for improving or changing them is essential if the new owner is to move forward successfully with a retraining program. Investing an adequate amount of time and ground handling into that transition period will yield many rewards in the years ahead and help the horse blossom in a new career.

“There is a growing interest in developing new careers for Thoroughbreds when their racing days are over,” says Garry Westergaard, horse trainer, breeder, clinician, judge, and owner with wife Pat of G.W. Equine Services in Sherwood Park, Alberta. “Some of these horses have the potential to be successful in many different disciplines if they are effectively reprogrammed so to speak, from the racetrack environment to their new careers. This transition, though, doesn’t always go smoothly as the ex-Thoroughbred racehorse can have some interesting and peculiar behaviour problems as well as physical issues that will need to be dealt with.”

According to an article written by Barbara Sheridan for Equine Guelph (Second Careers for Racehorses: The Transition from Racetrack to Ribbons), each year the racing industry ensures a steady stream of horses that have found themselves at the end of their racing careers. On average, ages can run from two-year-olds (with only one season of racing) to four and five-year-olds, while some with steady, lucrative careers retire from the track at six years and up.

The reasons for their move to another career may vary anywhere from a slowdown of their speed, to less frequent wins, to owners deciding to downsize their racing barn in the face of high overhead costs. Sometimes, these young retirees have some physical issues that must be addressed before any retraining can get underway.

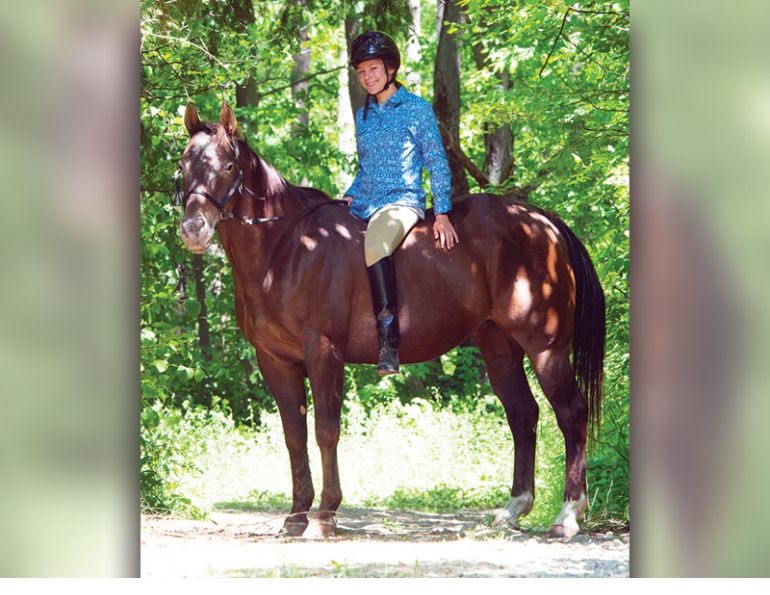

There is a growing interest in developing second careers for Thoroughbreds. When their racing days are over, many have gone on to become pleasure and trail riding partners, competition mounts in a range of disciplines, and even Olympic athletes. Photo: ©Shutterstock/Cheryl Ann Quigley

In California, Priscilla Clark operates Tranquility Farm in Tehachapi where she has rehabilitated, retrained, and adopted several hundred off-the-track Thoroughbreds.

“Other than the fact that most have an unsoundness, which must be cared for before retraining can begin, a commonality is the inability to focus upon a caregiver or trainer,” she says. “By focus, I mean a willingness to learn basic skills like leading or standing quietly. Riders who do not have a background in riding racehorses will expect this ability to already be instilled in a mature horse, but this is not the case. Often training goes poorly at the beginning because this fundamental element is lacking.”

Clark says that the key to understanding this is to look more closely at the traditional upbringing and handling of a racehorse. Sometimes they are weaned early. They are broken to ride early in life and start racing as two-year-olds. Economics drives the need to get racehorses performing and winning - or sold to recoup investment.

“This does not make for a culture which gives the horse much opportunity to learn and mature,” she says.

Horses come from the track with a unique set of experiences and behaviours. Once rehabilitated to a slower lifestyle with a training program geared to their individual needs and temperament, they can blossom in a new career. Photo: Skyline Photography

Horses coming off the track are not only energetic, but also highly reactive. They have been handled by a variety of people and ridden by different jockeys and exercise riders. None of this has allowed for the development of a horse/rider relationship or teamwork.

“I find that it is very important to get into their minds so they think that they are part of the team. And once I have gained their confidence, most of them are very easy to work with,” says Westergaard. “I’m a great believer in doing a lot of ground work with horses while they are in training before I start riding them, as well as during the time that they are being ridden.”

He says that ground work includes lunging and long-lining. “These techniques are used to develop their mouths, supple them, and teach them how to handle their feet. I will get the horses doing lots of walking, trotting, and cantering to develop their gaits, as well as two-tracking, side passing, stopping, and backing up. In short, I get them doing a lot of the same manoeuvres that I will do when I am riding them.”

New owners need to remember that these hot-blooded horses are trained to run. Some, though, may appear to have a quiet temperament, so people assume they handle situations calmly. But when incidents arise that are outside the normal routine, even small things, Thoroughbreds can react extremely swiftly – some might say explosively - putting those around them in danger.

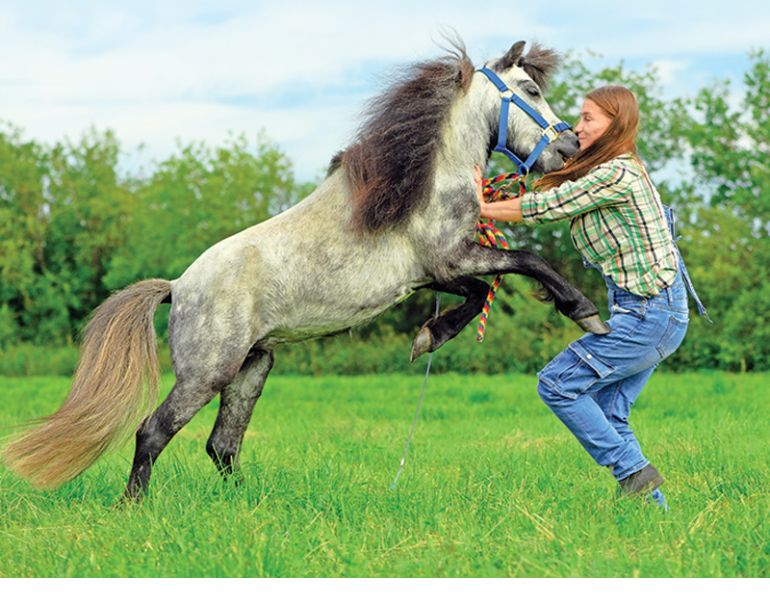

Trainer Garry Westergaard does a lot of ground work both before and after riding has started. He uses lunging and long-lining to supple the horse, develop the mouth, and teach the horse how to handle its feet by doing the same manoeuvres on the ground that he will do when riding. He begins work under saddle when the horse is comfortable with ground work. Photo: Kirsten Quist Photography

“New owners must be aware that these horses are hot blooded, bred and trained to race and run,” says Carmen Kramer with New Stride Thoroughbred Adoption Society in Abbotsford, BC. “Some off-the-track Thoroughbreds are seemingly ‘laid back.’ However, often unexpectedly something triggers the breeds’ sensitivity and flight reactions which, in inexperienced hands, can result in challenging circumstances.”

As Thoroughbreds are rehabilitated to a slower lifestyle, it is important to understand that consistency and steadiness are vital assets in the training process, bearing in mind their own individual temperament and personalities.

Clark says in her online article Retraining a Former Racehorse that many horses come off the track in peak condition after suddenly sustaining a career-ending injury. Typically, some of the physical conditions that may require veterinary attention include soft tissue issues surrounding tendons and ligaments, joint problems, or issues surrounding the hock, stifle, or back.

“This means they still have abundant energy and can become very frustrated by the sudden lack of strenuous exercise,” she says. “For these horses a diet of high quality mixed forages such as grass and alfalfa hay without a grain ration will help to calm them down. A probiotic product to help them digest roughage is very beneficial. If you want to add joint supplements or anti-inflammatory products to the ration, mix them with a high soluble fibre product that is low in carbohydrates. Most major feed companies now produce a suitable low-starch ration, and have an equine nutritionist on staff to help the owner determine the best overall diet. If you have access to fresh grass, turning them out in a small area or hand-grazing for a few minutes each day will provide welcome relief from boredom and add variety to the limited diet. It will also make your time together something the horse looks forward to.”

The horse must learn to pay attention and look to his handler for guidance. Once he has gained their confidence, Garry Westergaard finds most horses very easy to work with. Photo: Kirsten Quist Photography

At the other end of the spectrum, Clark explains, is the thin, used-up horse that has run to exhaustion or who may be having a “crash” due to digestive problems or withdrawal from anabolic steroids. For this horse the forage diet will not be sufficient, and the addition of a high-fat, high-protein ration will work very well together with supplements recommended by a veterinarian. She cautions about rehabilitating a thin horse - too much food too soon can lead to digestive disorders and colic. She recommends seeking veterinary advice on the best course of action.

Varied, nutritious food is all part of your horse’s fresh start. After a medical check and any adjustments based on your vet’s recommendations, the horse will welcome some vacation time to adjust to his new surroundings and relax mentally and physically. But even that can come with a few challenges.

“Thoroughbreds are bred to run,” says Kramer. “Many are very keen on their old jobs and take some time to realize their new life is not as fast-paced and exciting as their previous life. Turnout is also something that challenges some. If the turnout area is large, it is often overwhelming for them, as is group turnout. Group skills need to be learned or relearned and this takes some time.”

“Group skills” means learning to find their place in a herd. When another of our mares, Sunny, returned from training, she was turned out with her family band, but things didn’t go well at first and she was excluded from grazing with the group. Even her dam drove her off. She kept to herself a good 20 metres away from any other horse. It wasn’t until the lower-ranking geldings began to graze with her that the other horses allowed her back in at the lowest level of the pecking order.

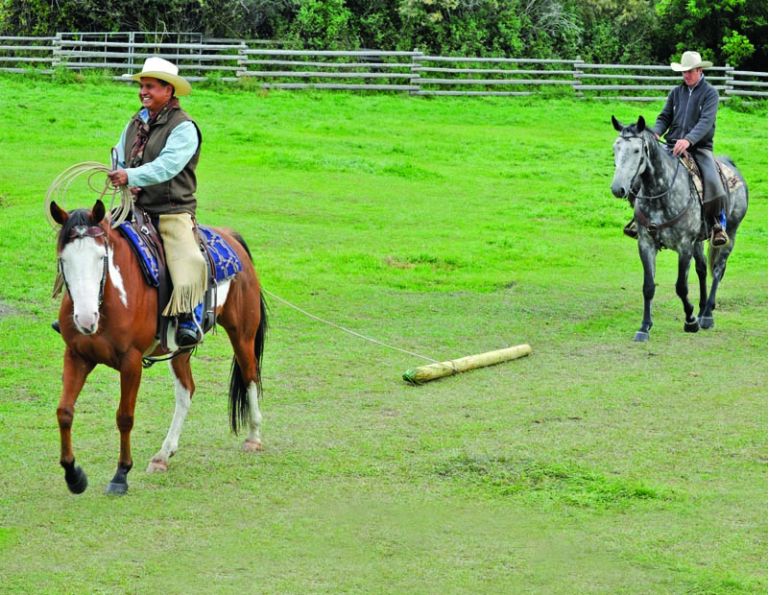

Garry Westergaard incorporates lots of transitions, circles, changes of direction, and other movements suited to each horse’s individual needs, both in the arena and outside in the open. Photo: Kirsten Quist Photography

There is always the potential for an accident or injury when a horse is being introduced to an established group. If the incoming Thoroughbred is still shod all around and is going to get some downtime in a paddock with other horses, remove the hind shoes to protect others wanting to get too close too quickly.

A dominant mare may drive the newcomer away and drive away others in the band trying to upstage the leader. The new horse will also behave defensively. In the process of rejigging herd hierarchy, feet can fly and teeth can grab mouthfuls of hair.

In the early days, it may be safer and more advantageous for the Thoroughbred to be turned out in a small, dedicated paddock where he has freedom to move, but can see other horses over the fence. Even then he needs to be prevented from fence running and doing any harm. If he frets too much an older, quieter companion turned out with him may be just the ticket to help with the adjustment.

No two horses are the same, and each Thoroughbred may have received different levels or intensities of training. Astute horse people know to watch for the subtle signs.

Off-the-track Thoroughbreds tend to have one-sided development due to racing in the same direction. These horses should be worked equally in both directions to develop balance and muscle tone equally on both sides. Photo: Kirsten Quist Photography

“We do notice, when we work with the horses, the ones that have had training other than ‘run fast with a rider on,’” says Kramer. “The horses tell us a lot about their background training and handling when we interact with them.”

New Stride adopts out an average of 12 horses each year. When horses come in, they are given time to settle in, and after several days the training begins with groundwork. Adoptions are approved based on age and experience of the new owner, the living facility for the horse, access to a veterinarian, and appropriate coaching and training services for the horse and rider. Plus, says Kramer, the adopting person must have a sackful of patience, consistency, and love.

What is important, says Clark, is to take the time to retrace the basic steps in training and give the horse time to develop confidence. “He must learn to lead in a quiet and straight manner, stand quietly at halter, tie, and basically develop trust in his handler. Along with trust, he must learn respect because for some obscure reason [racetrack] grooms often let the horse lean all over them while leading. This makes for a horse that does not know the boundary of his physical space and that of the handler. Some horses respond quickly to learning ground manners while others will take more time. But almost all former racehorses need this foundation before progressing to a new career.”

Clark stresses the importance of safety on the ground. New owners of off-the-track Thoroughbreds will need to remember that the horse has been under restraint most of the time and may not know the boundaries of good behaviour when restraint is slackened.

Given time to transition both mentally and physically, the former racing Thoroughbred will begin to understand his new life and what is expected of him. Photo: Skyline Photography

“Rearing or spinning while being led will frighten many new owners when they do not realize the horse has seldom been given much freedom of movement other than running on the track,” says Clark. “All off-the-track Thoroughbreds should be ground-worked extensively to the point where they are quiet and confident before the new owner begins work under saddle.”

Clark comments that a frequent cause of accidents is tying the horse. In some racetrack facilities, horses are tied at the back of their stalls on a single tie bar. They have not seen cross-ties and they have not been tied in an open area. It therefore would be appropriate for horses to be tied in the manner in which they are used to for grooming and tacking up, then gradually make changes according to the preferred location. A quick release tie is essential and the horse should never be left unattended.

“Thoroughbreds have been bred to react quickly to stimulus and are easily upset being tied where there is activity until they have had sufficient time to become accustomed to it,” says Clark. “This is one of the more time-consuming lessons for the horse, but an essential one.”

Executive administrator Wendy Muir of LongRun Thoroughbred Retirement Society in Toronto, Ontario, says that the horse’s diet must be adjusted to match their new work schedule.

When done well, the evolution from racehorse to riding partner brings out the best in the horse, and is a rewarding and educational experience for the trainer and rider. Photo: Skyline Photography

“Too little and they lose weight rapidly; too much and they can be more aggressive and spirited than their new owner can handle,” says Muir. “Racehorses have had shoes on most of their lives so new owners must realize they can’t just throw their horse out in the paddock or start their riding barefoot. Most people [also] don’t realize that horses need regular dental care, and deworming is very important.”

All horses at the LongRun facility are understandably different from one another given the fact that they have had different levels of training and care. The priority is to give them a comfortable, safe, and consistent environment to avoid confusion and encourage a quick adaptation to their new life as they learn to relax and enjoy new food and new routines.

One successful Thoroughbred that entered the LongRun facility was Exultation (aka Down By The Docks) now owned by Olympic eventer Jessica Phoenix of Cannington, Ontario. Phoenix, as a competition coach and specialist in eventing, operates Phoenix Equestrian and of some 35 horses in her program, half of them are Thoroughbreds.

“You have to treat them all individually and do what is best and what is right for each horse,” says Phoenix. “We’ve got some four-year-olds in the barn right now and it’s just always fun to get them and play with them as babies. It’s rewarding to see the change that they can make every day. They come along with their top lines and their performances, so it’s very exciting.”

Seven On Friday lost his sight in an accident at the starting gate, and will reside at Toronto’s LongRun Thoroughbred Retirement Society for the rest of his life. Photo courtesy of Longrun Thoroughbred Retirement Society.

Muir stresses that new owners must remember that off-the-track Thoroughbreds are intelligent, good-feeling horses that need to be treated with respect and patience.

“Their trust has to be earned and it sometimes takes a while,” says Muir. “They all need a certain amount of downtime to become ‘horses’ again instead of elite athletes. If the adopter doesn’t feel experienced enough, then they should retain a coach or enlist the help of someone who has dealt with Thoroughbreds before.”

Muir has worked in the industry for 40 years and has seen many changes, some of which are improvements in horse care.

“Of course with advancements in science, feeding is no longer hay, oats, and salt,” she says. “Nutrition is very big these days. Since the Thoroughbreds are now properly regarded as athletes, we have chiropractors, massage therapists, and acupuncture available for them. There are nebulizers for their breathing, electromagnetic blankets for their aches and pains, and better diagnostics for those hard-to-define problems. Advances in surgery mean injuries that used to spell retirement now mean rest and rehab. Mental state is also more closely followed with some horses being provided with ‘vacation time’ to rest and refresh. Negatively speaking, some medications can mask true problems, and horses can be pushed farther than they are able to take.”

Twenty-two year old Major Zee, the oldest “pensioner” at LongRun, with his sponsor, Donna Ralph. Photo courtesy of Longrun Thoroughbred Retirement Society

The LongRun facility has about 75 horses in their care during any given year, with about 50 in the program at any one time. Between 25 and 40 adoptions are completed each year.

“Some are adopted quickly by competent horse people, while others undergo downtime and rehabilitation,” says Muir. “Any horse that is up for adoption as a riding horse undergoes some level of retraining. We like them to be able to walk and trot on a loose line and be comfortable around other horses so potential adopters can ride them.”

Those early days of retraining go a lot smoother once the horse is healthy, happy, and has developed a level of confidence in his new surroundings.

“Start a leading, lunging, and even ground driving routine to retrain the horse to saddle,” says Clark. “Teach the horse where his feet are and that he can move them slowly and focus on the ground. This seems so basic, but a racehorse is always looking down the track and moving forward. He doesn’t know about a full halt, small slow turns, changes of direction, or other incremental movements that we take for granted in a saddle horse.”

Jocelyn Inglehart can’t say enough wonderful things about her ex-racehorse, My Mom Is Hot. Photo courtesy of Longrun Thoroughbred Retirement Society

A good exercise, and one in which the horse learns to work with his handler and pay attention to his feet, is for the horse to be walked over a series of poles on the ground or cavalletti poles at their lowest height, properly spaced for a walking gait. Do this in a small area where the horse is well contained for safety and where turning, stopping, and circling will keep him continuously focused. The exercise can progress to working over poles on a lunge line where adjustment can be made for trotting over the poles. Before long, you will start to see a learning curve as the horse picks up on the intent of the program and starts to show enjoyment in each of the small but important challenges.

Cavalletti and ground poles in various combinations and formations are wonderful and interesting small challenges both as ground work and later during the process of riding.

Be creative with ground exercises – in addition to poles, use bales of straw, cones, barrels, or whatever is at hand to create a walking course that might resemble a trail class. The intent is for the horse to concentrate on where he is putting his feet and learn to turn, halt, or back up on command. The added benefit from all the different props is that he will become accustomed to new obstacles in his world and not fear new shapes, smells, and sounds.

Lunging is one of the most invaluable training techniques, not only to rehabilitate horses coming off the track, but to start young horses or restart horses coming off some downtime due to injury or sickness.

Jane Avril was so nervous while racing that she couldn’t breeze, but the lovely bay mare is now eventing at the Pre-Training level. Photo: ©Bailini, courtesy of LongRun Thoroughbred Retirement Society

The big plus to all this ground work is that the horse will begin to look to his handler for guidance and instruction. This is a big change from his past life where he learned to bolt out of the starting gate and then run like a bat out of hell. Now he has to slow down, think, listen, and pay attention to twists and turns. The learning curve begins when he no longer sidesteps at all these strange shapes but starts to anticipate with some enjoyment what he’s going to do next. And the bonus is the bond that is developing with the trainer; it’s becoming a twosome affair that will quickly lead to continuing the training by riding the horse as a willing team member.

Westergaard begins riding once the horse is comfortable with the ground work program.

Olympic eventer Jessica Phoenix of Cannington, Ontario, has enjoyed great success with ex-racehorses, most notably Exponential, a dark bay Ontario-bred colt that raced at Woodbine and Fort Erie from 2000 to 2003. At the 2010 World Equestrian Games, Phoenix and Exponential helped their Canadian Eventing team claim the silver medal. They finished 22nd individually at the 2012 Olympic Games in London, the only Canadian to complete all three phases of the eventing competition. Photo: Shannon Brinkman Photography

“I find that when I start riding these horses, often they are comfortable with the ground work program and they are very easy to collect,” he says. “From then on we work on transitions, lots of circles, and whatever manoeuvers are needed to deal with each horse’s individual needs. In the riding program, I like to work in the arena and outside in an open area. I also like to ride them when I am teaching riding lessons, so they realize that they aren’t in a horse race when they are with other horses.”

Westergaard’s goal when riding is to get the horse soft and supple in the mouth. He uses many different snaffle bits and, at times, a curb bit with a cricket to help the horse relax its jaw. He may also use a light bosal along with the bit, and his talents include the design and construction of these unique nosebands used on the classic hackamore.

“When the horses are working well, they will be offered for sale or, if they are client-owned, I like to work with the horse and rider for a period of time and then they will move on to whatever discipline they wish to pursue, such as three-day eventing or dressage. They can also be developed into excellent ranch horses. If the horse is of suitable temperament it will work well in the Western speed events such as gymkhana and barrel racing.”

The transition from racehorse to an equestrian mount is a feel-good journey that brings out the best in the horse while enriching the trainer’s knowledge and experience. Time invested during the important transition phase will produce a wonderful working partner for a lifetime.

Her days at the track now a distant memory, Daisy (centre) grazes with barn mates while two young black tailed bucks spar in the background. Photo: Margaret Evans

“I think more trainers realize what they are getting into and how much real work is involved in basically restarting a horse,” says Clark. “There are no short cuts in making a horse safe to ride.”

Clark says that there is no set pattern of development in training the off-the-track Thoroughbred. When the former racehorse has gone through all the steps and is progressing comfortably, it will be up to the new owner to decide when the horse is ready for an experimental trail ride, schooling show, or clinic in a new environment. Whatever discipline is chosen will be an inviting and exciting road, as they will have reached the starting gate that opens to a new future and a wonderful lifelong partnership.

Main photo: ©Shutterstock/Ann Quigley

This article was published in 2018. Some of its details may be outdated.