By Shelagh Niblock, BSc.Ag., PAS

Buying hay for your horse can be a challenge whether you buy it a few bales at a time or purchase a year’s supply when it becomes available in the summer. Supply, price, and quality have always been important parameters to consider when buying hay for horses, but now, more than ever before, horse owners are becoming aware of the importance of the nutritional components of the hay they feed. Many hay dealers will provide you with a laboratory analysis for the hay they have for sale. If they do not, or if you grow your own hay, you’ll need to sample it yourself for lab analysis.

TAKING THE HAY SAMPLE

The first challenge in getting hay analyzed for nutrient content is obtaining a representative sample. Ideally, sampling hay involves the use of a hay drill suitable for “coring” sufficient bales to get a representative sample. Sampling at least 6 to 12 bales off the stack is recommended to get an accurate sample. While coring bales with a proper hay drill is recommended, it is possible to take grab samples (handfuls) of a number of bales (at least 10 to 12 different bales) if you don’t have a drill. Whether you have cored bales or taken grab samples, the hay you have collected off the stack needs to be well mixed in a large pail and then sub-sampled. The sub-sample should be of a sufficient amount to fill a large Ziploc® bag.

If your hay dealer will not provide you with a lab analysis of their hay, you can sample it yourself using a hay drill (pictured) or by taking grab samples. Regardless of the sampling method, samples should be taken from a number of bales to get an accurate sampling of the entire stack of hay. Photo: Pam MacKenzie Photography

When you have your hay sample ready, it should be packed in waterproof packaging and either personally delivered or sent to the lab of your choice. Make sure you have included your name and phone number or email address so that you can be notified when your hay analysis is complete.

Analysis options can include wet chemistry or NIRS (Near Infrared Spectroscopy), either of which would be suitable for the analysis of horse hay for the basic nutrients such as moisture, dry matter, crude protein, non-structural carbohydrates (NSC), and sugars.

Analyzing hay for trace minerals should always be done using wet chemistry methods. While NIRS can be highly accurate for determining most nutrients in a hay sample, it isn’t recognized as being sufficiently accurate for trace mineral analysis.

Related: Feeding Myths & Misconceptions

READING THE LAB REPORT

As Fed versus Dry Matter Basis

At first glance, your hay analysis report may be intimidating. You will see a large collection of numbers, usually arrayed in two columns labelled as “As Fed” and “Dry Matter Basis.” For the purposes of evaluating the hay for your horse you will most often consult the “Dry Matter Basis” column. Both sets of numbers represent the actual amount of the specific nutrient in the hay, but the “As Fed” column is reported with the values expressed as a percentage of the feed including the weight of the moisture in it. The “Dry Matter Basis” column is reporting the nutrients expressed as a percentage of the feed without the moisture included. Every feedstuff has moisture...some have more than others.

In order to accurately compare the inputs into your horse’s diet of one feedstuff relative to another, it is important to compare them on a dry matter basis so that the nutrients they contribute are not being “diluted” in percentage by the moisture present in the feed. Ideally, grass or alfalfa hay should be 90 percent or more dry matter, indicating the presence of 10 percent moisture or less. More than 10 percent moisture in a hay sample could indicate a higher risk for mold or heating in the bales.

Crude Protein

Crude protein is an estimation of the total protein content of a feed. It is determined by analyzing the nitrogen content of the feed and multiplying the result by 6.25. Protein in some feedstuffs such as grass silage or haylage can be further differentiated by criteria such as protein digestibility and protein quality. Generally, grass or alfalfa hays that are 90 percent or higher in dry matter, and were harvested at a pre-bloom or pre-boot stage, contain a high quality protein of superior digestibility.

Your horse’s requirements for crude protein and digestible energy in the hay depend on his age, amount of work, and any pre-existing metabolic conditions, as well as the other feeds you are including in his diet. Photo: John Donges/Flickr

The requirement for protein in horse hay will vary depending on what other feeds are being offered, the work level of the horses, and their metabolic state, i.e. growing, mature, breeding stallion, lactating mare, etc. The protein requirements of horses are well documented in the National Research

Council Nutrient Guidelines for Horses, available online at: http://nrc88.nas.edu/nrh/.

The hay you buy for your horse should have a high enough percentage of crude protein to ensure that your horse’s maintenance protein requirements are being met. Ideally, this means finding hay with crude protein in the range of 10 to 14 percent on a dry matter basis (DM). Hay that is lower than 10 percent in crude protein could possibly have high non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) values so use caution in buying low protein “maintenance” hays.

ADF, NDF, & Lignin

The terms ADF and NDF stand for Acid Detergent Fibre and Neutral Detergent Fibre respectively. These terms refer to the cell wall portions of the forage that are made up of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. These values are important because they give an indication as to the ability of the horse to digest the hay to its component nutrients. As forage matures, the ADF, NDF, and lignin values tend to increase. As ADF, NDF, and lignin increase, digestibility of hay usually decreases. The energy measurements such as digestible energy (DE) reported on your hay analysis are calculated using the ADF, NDF, and lignin values.

ESC, WSC, Starch, & NSC

The values for ADF, NDF, and lignin are all used to help quantify the cell walls in your hay test. The terms ESC, WSC, Starch, and NSC are all used to describe the cell content portions of the hay. The terms ESC and WSC stand for ethanol soluble carbohydrate and water soluble carbohydrate respectively. ESC is a measure of the very simple sugars and WSC is a measure of the ESC plus the more complex sugars present in the hay sample. The difference between WSC and ESC is essentially the complex storage sugar called fructan. Forage testing labs are not yet testing specifically for this sugar but it is possible to get an idea of the fructan content of your grass hay by subtracting the ESC value from the WSC value. The difference is the approximate percentage of the fructan in your hay sample. There is increasing evidence from ongoing research that fructan is a carbohydrate compound that may be causing significant health issues for our metabolically challenged horses.

Starch is a complex form of sugar that the plant may use to store carbohydrate. Most cool season grasses do not store plant carbohydrates as starch and so it isn’t usually a very significant component of hay.

Related: Hay, Haylage and Silage: What's the Difference?

The sum of WSC (equal to roughly the ESC and fructan content of the hay) and the starch is equal to the NSC or non-structural carbohydrate. NSC is the number commonly used by equine nutritionists and horse owners as a parameter for “safe” hay for metabolically challenged horses. The rule of thumb for feeding a horse with health issues such as insulin resistance, Cushing’s Disease, or Equine Metabolic Syndrome is sourcing hay with an NSC value of 10 percent or less on a dry matter basis.

Nitrate

Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

Nitrate is a nitrogen containing compound that can be toxic to horses if ingested in large enough amounts. Hay can become high in nitrate if it is irrigated by high nitrate water, excessive applications of nitrogen containing fertilizers, or if the hay field is infested with weeds that are high in nitrate. High nitrate can cause gastrointestinal irritation, colic, and/or diarrhea in your horse, but the biggest risk from nitrate is that of nitrite toxicity.

Nitrate is converted to the more toxic nitrite in the hindgut of the horse by the fibre fermenting bacteria. Once converted, the nitrite travels through the gut wall into the bloodstream where is interferes with the ability of the horse’s red blood cells to carry oxygen. Clinical signs of nitrite toxicity are laboured breathing or panting, ataxia, convulsions, grey or bluish mucosa, abortions in pregnant animals, and death. Ensure that nitrate levels on your hay test are low or negligible.

Digestible Energy (DE)

Energy is frequently described as being a nutrient, but in actual fact, it’s a measure of the “fuel” provided to the horse by other nutrients. DE, or digestible energy, is a calculated value that is an attempt to quantify the amount of “fuel” provided by a feedstuff. On your lab report, DE is a computer derived calculation that has taken into consideration all the nutrients contained in the hay.

Digestible energy is quantified in terms of calories, or in horse nutrition, megacalories (MCal), and is a unit of measurement equal to one million calories. Calories are the units of energy that represent a standardized amount of heat released when organic compounds undergo combustion in animals’ bodies.

Comparing feedstuffs for your horse on DE alone can be misleading. A higher fibre, lower digestibility energy hay might be suitable for an overweight horse because it might limit intake, but DE doesn’t give us a good indication of the digestibility of a forage or how readily the horse will eat it. High fibre, lower DE forages can still yield significant energy to our horses through the fermentation of the fibre fractions by the beneficial microbes that colonize in the hind gut.

Related: The How & Why of Soaking Hay

WHAT IS A GOOD HAY TEST?

One of the most important criteria in buying hay, regardless of the lab analysis, is the quality. Make sure your hay is clean and free of weeds and extraneous material, and never feed hay that is moldy or hot to the touch when you open a bale. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

Now that you have your hay test in hand, do you know what those numbers need to be for your particular horse? A good hay test for your horse will depend on your horse’s age, amount of work, the weather, and whether he has any pre-existing metabolic conditions. We all know that insulin resistant horses have a low tolerance for high sugar hays, but if your insulin resistant horse is a mature pasture ornament he may not require the higher protein level commonly found in low sugar hays. It is important to use some common sense in selecting hays and balance your horse’s diet for the hay in your barn by making it a part of a more varied diet including other safe fibre sources if it doesn’t exactly fit your horse’s unique set of requirements.

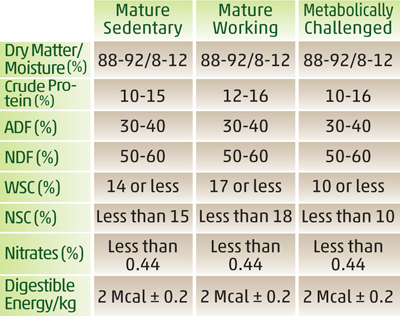

Guidelines

The following table provides some guidelines to follow when interpreting your hay analysis. Remember, these are guidelines only and a lab report with a nutrient that falls outside these guidelines is not necessarily a cause for major concern.

Grass Hay

One of the most important criteria in buying hay, regardless of the lab analysis, is the overall quality. Is it clean and free from weeds and extraneous material like sticks? The best hay analysis in the world is of secondary importance if the hay is moldy or hot to the touch when you open a bale. Remember, regardless of your hay test, your horse will be healthier if you follow some basic feeding principles including feeding frequent, small meals and providing ample fresh water.

Related: Fast Forage Switches Not Recommended for Horses

Related: Free-Choice Feeding is Not the Answer to Equine Obesity

Main photo: Robin Duncan Photography