Contributed by Soul of Canada

Today the gentle giant draft horses are seldom seen, almost lost in a world of high-speed, noisy machines that require industrial fuel to perform. Yet we are occasionally reminded of their impressive strength, substance, and style when we see a team perform in a parade, a show ring, a movie, or a heritage park.

Only a century ago, draft horses, mules, and oxen were almost everywhere, providing a practical, dependable, and renewable power source for pioneer-era industries such as agriculture, railway building, large-scale excavation and earth-moving, mining, logging, and road construction. In fact, before 1910, at least 90 percent of all public works, agriculture, and resource industries relied on “horse power” to complete jobs both large and small.

The market for farm equipment created a demand for larger, stronger horses to power the new equipment. Photo courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta

Traditional Agriculture

For millennia, grains, fruits, and vegetables were produced manually by sowing seeds and using a scythe to harvest the crops. Hand-flailing the straw to remove the grain on the ground was a slow and inefficient way of processing. Innovations in farm equipment significantly increased the productivity of North American farmers. Double-width harrows, steel plows mounted on wheels, mowers, binders, threshers, and combines reduced the need for manpower, while dramatically increasing the horse power required to operate them. Improvements in harnesses and hitch design also increased efficiency. The western market for farm equipment created a demand for stronger and larger horses to power the new equipment. Horse, farmer, and machine began working together to plant and harvest the crops. The last half of the 19th century saw draft horse breeding become both essential and profitable.

Draft horse breeding programs in Canada flourished during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in response to the agricultural sector's demand for more horsepower. Photo courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta

Horse Breeding

Horse breeding programs flourished in the late 1800s and in the early part of the 1900s. During this time, many grain farms had more horses (as many as 10 or more) than people, with each horse working an average of 600 hours per year. According to Wetherell and Corbet’s Breaking New Ground – A Century of Farm Equipment Manufacturing on the Canadian Prairies, there were 55,593 farms harvesting over 43 million bushels of wheat, oats and barley in the Canadian Prairie provinces in 1901.

Around this time, newly created agricultural and veterinary colleges began producing more educated farmers. Corresponding developments in the breeding, feeding, and care of horses led to a horse population explosion. With the increase in the number of acres being cultivated, farmers needed more horses to do the field work. Grant MacEwan, author of Grant MacEwan’s Illustrated History of Western Canadian Agriculture, states that by 1911, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba had a combined total of 1,194,927 horses, which works out to be an average of six horses, including juveniles, for every one of the 204,214 farms in the three provinces.

The number of horses in Canada peaked in the 1930s. In 1930, Saskatchewan was home to over one million horses, but the next year the population began to drop, and by 1951 only 304,000 horses remained. This decrease in population was a direct result of the introduction of high-tech, mechanized agriculture.

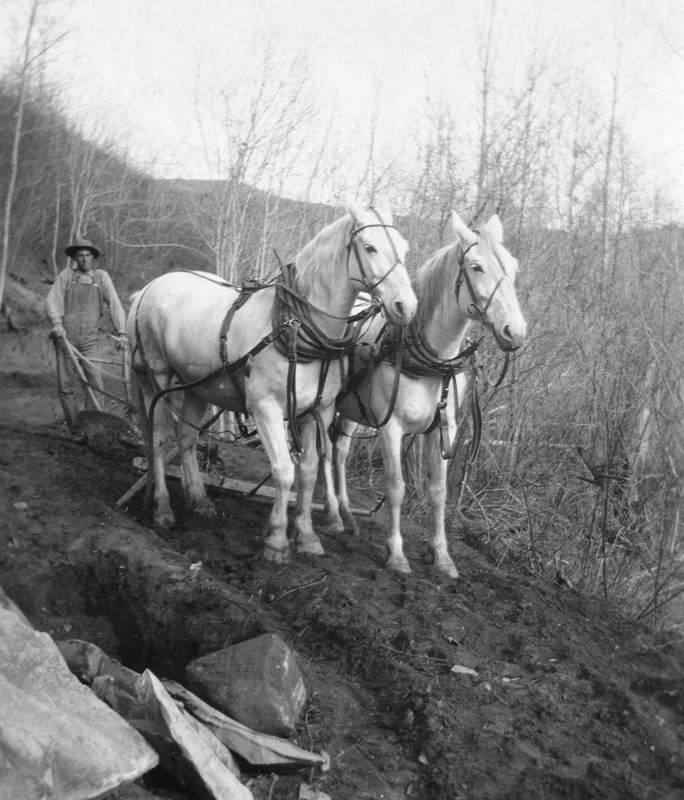

Road building in the early 1900s began with clearing the path of obstructions such as trees, bushes, and rocks. Then the roadway was leveled by means of a horse-drawn plow, like the one Frank Gano used in 1917 to build a road west of Wainwright, Alberta. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives

Competing Mechanical Workhorses

The Industrial Revolution was partly responsible for both the rise and the collapse of the heavy horse in North America. The changes in agricultural technology peaked in the latter part of the 19th century. Demand for draft animals was spurred by growing transportation, construction, and agricultural needs.

The year 1917, when the Ford Motor Company introduced the Fordson Tractor, saw the beginning of the trend moving away from horse power in favour of farm mechanization. The horse lost the dominance of the streets to the automotive industry rather quickly. As for the contest for the agricultural fields, the horse fought tenaciously but eventually yielded in many cases to steam and gas tractor power.

Since that time, the draft breeds have not only stabilized in numbers, but also once more enjoy a thriving trade. The stabilization of the draft horse population can be attributed to the dedication of draft horse breeders, as well as the decision of the old order Amish to reject tractor power in the fields. Today on small Amish farms the horse plays its traditional role as the equine tractor that burns home-grown fuel and raises its own replacements. The Amish in Ohio and Mennonites in Ontario are also producing new horse machinery in order to provide people with superior equipment. The equipment is invented, then tried and tested on their farms before it is sold to the public.

This 1920s Jackson Construction Company four-wheeled pull-grader required two teams, an operator, and a teamster. Road grading crews such as this one laid the foundation for the network of roads and highways that stretch across Alberta today. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives

Today, there are about 1500 Amish living in Canada, the majority in southwestern Ontario. In 2006, a small group of families established homes in Manitoba near Gladstone, far from the perceived dangers of industrialization and nuclear power plants. They all continue to conduct farm work with horses as their sole source of power and still travel by horse and buggy.

The present trade for heavy horses is made up of several niche markets. Draft horses’ power and beauty have more than a little to do with this resurgence. The multiple hitch, once used to pull plows and combines, now finds itself hitched to commercial wagons in parades and big fifth wheel wagons at fairs. On western cattle ranches, horse teams are still used to haul feed to cattle.

Many of Canada’s original working horses were of indeterminate ancestry, a mix of whatever breeds were available. Where there was a choice amongst the registered breeds, the farmers, freighters, and contractors were decided about their preferences. As Grant MacEwan describes it, “Nobody was neutral; either a man favoured the flat-boned, hard-hocked, big-footed Clydes with [their] straight and bold action, or he declared for Percherons or Belgians with their huge middles, powerful muscles, and phlegmatic dispositions.”

In 1916, the Bar U Ranch in southern Alberta, owned by George Lane, was home to 700 registered Percherons, among them this six-horse team and 400 broodmares. Photo courtesy of Parks Canada

The Percheron

The Percheron derives its name from the small French district of La Perche, southeast of Normandy. It was the first of the draft breeds to arrive in the Americas in 1839. The Canadian Percheron Association was formed in 1907 and its website states: “In spite of mechanization and automation, the Percheron breed has survived and, in recent years has increased tremendously in popularity and numbers.” In 1962, there were 129 Percheron foals registered for the year; in 2008 there were 918 registered and their numbers continue to increase. Percherons have historically been used as both freight and farm horses; the Percheron makes an excellent hitch horse due to its immense strength and stamina, and is lauded for its good temperament and work ethic. The Canadian Percheron Association was formed in 1907. As of December 2010, 29,188 stallions and 42,951 mares were registered with them. Today, Percherons can be found working in fields, forests, and even Canadian historic sites such as Bar U Ranch in Alberta.

Originally bred for warfare, the Belgian`s steadfast nature and physical strength make it ideally suited as a workhorse. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

The Belgian

The Belgian originated as a working horse in the lowlands of Belgium, and became sought after for warfare; often weighing well over 1600 pounds, the animal could easily carry armour-laden soldiers in the battlefield. These giant horses were known to the Romans, and Julius Caesar remarked on their endurance and willing nature. The Belgian government produced a National Stud Book in 1886, and the first Belgian arrived in Canada in 1902, coming to Quebec. The Canadian Belgian Draft Breeders’ Association was incorporated in 1907, and since then there have been over 37,000 registrations. Their name changed to the Canadian Belgian Horse Association in 1934. Registrations hit a low in the early 1950s but have since rebounded to mid-1930 levels mainly thanks to Amish and Mennonite communities that are recognized for their dedication to Belgians for farm use. In 2011 there were 827 members in the CBHA, 335 Belgians registered and 303 Belgians transferred between owners.

Originally used for farming, mining, and logging, today the Clydesdale can often be seen in parades and at heritage parks. Pictured are the famous Budweiser Clydesdales hitch on display in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Photo: Pam MacKenzie Photography

The Clydesdale

The Clydesdale is Scotland’s heavy horse, dating back to the beginning of the 18th century when Flemish stallions were brought to the Clyde Valley of Lanarkshire. The Clydesdale is ideally suited for draft work as it is known for its willingness and high energy. Historically this big breed was used for farming but was powerful enough to work in coal mines and logging camps as well. The Canadian Clydesdale Horse Association was formed in 1886. According to horse historian Merlin Ford, during the 1920s approximately 18,000 Clydesdales were registered in Canadian stud books; however, the total Clydesdale population would be a fair bit higher since the stud books include only the foals that were born and registered, and does not factor in the number of unregistered mature horses. As of December 2010, a total of 34,929 stallions and 73,516 mares were registered with the Clydesdale Horse Association of Canada.

The Canadian is good-natured and versatile, and known for its exceptional suitability as a driving horse. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

The Canadian

The Canadian breed may be one of the best kept secrets of the twentieth century but was well known to American colonists. The Canadian horse traces its ancestry to stock brought to Acadia and New France in the 17th century, when Louis XIV sent two stallions and twenty mares from the royal stables of Normandy and Brittany. In the mid-1800s, the Canadian horse population exceeded 150,000, but due to the desire for larger draft breeds, and advances in farm machinery technology, their numbers decreased throughout the 1900s. Canadian breed numbers waned further during the war years, and by the early 1970s there were only 400 left in existence. However, thanks to the efforts of the Canadian Horse Breeders Association and committed breeders across Canada, the breed’s numbers are rising. As of December 2010, there were 13,187 Canadian horses registered with the Canadian Horse Breeders Association. The versatile Canadian is represented by almost all types of equestrian disciplines, and is particularly well-known for their driving ability.

THE RETURN OF THE HORSE

Horse Logging

When Canada was settled, logging with horse, mule, and oxen was the economic basis of the growth of many towns. However, as machines took over the harvest of trees, the skills and benefits of logging with living horse power was lost.

Today, we have become aware of the damage that huge vehicles do in the forests, which includes altering water resources, compacting soil, and destroying wildlife habitat. In the logging industry, increasing environmental concerns have bolstered the use of horses and mules as the machines of choice. Concerned logging operators have reverted to the practice of using horses, as pre-selected trees can be cut and then hauled out with chain and harnessed horses, leaving only hoof prints and skidding trails in the ground, as compared with the tracks of a 10,000 pound tread skidder.

A team of horses can pull upwards of eight tons of timber a day, and causes less soil compaction and destruction of wildlife habitats than heavy machinery. Photo courtesy of Soul of Canada

Not only can a team of horses pull upwards of eight tons of timber a day, but the animals also can move on terrain inaccessible to machines, work quietly, and consume and recycle natural products.

In Prince Edward Island, a horse-logging project involving several skilled teamsters is underway in provincial forests. Teamster Kevin Taylor notes that: “Horse logging is very healthy for forest maintenance. What we hope to establish in the bush is a series of unevenly aged trees. It’ll be constantly an ongoing process where you go in and take out older trees and give room for new ones to establish. It’s part of the management cycle. Using horses in the winter forest keeps the wood intact. When you come in here in the spring, you’d never know there had been anything in there, like you would if there had been a tractor. There won’t be a mark in the woods.”

Peter Churchill, a horse logger from Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, uses one horse in the bush, which requires moving very little brush. He describes his involvement as select logging for a specific purpose, not necessarily a monetary purpose. “I like this very well because horse logging is not a volume business. For the landowners where I work, and on our own property, the motivation is low impact on our forest,” says Churchill. “We do not need huge mechanized equipment.”

USING HORSE SENSE TO AVERT WORLD CRISIS

Energy and Food Security

A growing number of small-scale farmers are concerned about sustainability and the use of fossil fuels. Many question what we will do when oil runs out or becomes too expensive. Solutions such as ethanol, biodiesel, or methane still require a level of technology that is not conducive to sustainable farming practices. Horse power could be one answer to this problem.

Advocates of industrial farming claim that without factory farms not enough food would be produced to feed all of the people in the world. The factory model of agriculture is often quoted as the most efficient way to produce cheap food; in fact, this could not be more untrue. What advocates of factory farms do not tell us is that the low cost of food does not take into account the true cost of production. Some of these hidden costs include degradation of our water, soil and air, damage to our health, and any of the impacts that are felt by the communities in which industrial farms are located. None of these costs are paid by the owners of factory farms but rather by the people who live in these communities. Billions of dollars are spent to mitigate problems created by agricultural industrialization. Damage to the air, water, and soil can only spell disaster for our species and no amount of money will be enough to fix the problem. Converting back to horse-powered methods will be a challenge but the cost will be far less than if we continue on the path of industrial agriculture.

Only a century ago, horses were the power source behind the agricultural, logging, mining, road and railway building, and large-scale excavating industries, as demonstrated by this draft horse team who tackled the job of massive earth removal for the Weed Creek Drop in Alberta in 1912. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives

With the aim of sustainability in mind, no tractor could possibly match the benefits of “animal power” over fossil fuels. As Jonathan Wright of The New Farmer School heartily asserts, “their [horses’] fuel comes from the land, from the sun. Their wastes go back into nurturing that land. They don’t come from a strip mine or an assembly line.” Horses make for healthy land as they run on hay which encourages farmers to employ perennial forage crops that build the soil with organic matter, protect the soil surface from wind and water erosion, and provide a living root system to sustain soil micro-organisms and fix atmospheric nitrogen. Horses eat grass or hay and return it to the farm ecosystem and economy as manure. The manure then returns to the soil to improve fertility and nourish the plants.

There are many other advantages of using animal power instead of industrial power. Draft animals tread lightly on the land and can work soil that is wet enough to bog down machinery. The horses’ hooves don’t create the compaction “dams” created by tractor tires, so wet areas tend to shrink rather than expand.

The Hornbrook Family of Mount Middleton, New Brunswick, has a six-generation farm with young children who will likely become the seventh generation. Their 680 acres, including 50 acres of grain, 300 acres of hay and silage, and 200 acres of bush, has always been looked after with horses. Calling the farm home are 40 Percheron horses, 60 milk cows, 50 beef cows, 30 ewes, and 15 sows.

“I didn’t have much luck using tractors in the woods,” says Adam Hornbrook. “The horses do a lot less damage in the bush than tractors do.”

The machinery used with draft animals is also far less expensive than mechanized machinery, and horses cost less than mechanized equipment to purchase and maintain. “Over a 10-year period our horses brought $10,000 to the farm in addition to the work they did. The horse purchases, harness, breeding and vet bills were offset by the sale of colts and teams,” Hornbrook says. The horse has a long working life during which one-third of the energy it consumes as food is reusable as manure, whereas two-thirds of the fuel energy used by a tractor is lost as heat and exhaust fumes.

The slower pace of a horse gives plenty of time for farmers to think while working, making it less likely that they’ll get hurt in an accident. Tried and true horseman Doc Hammill affirms this, saying, “One of the things I've learned over time is that the truly great teamsters rarely – if ever – have upset horses, close calls, mishaps, or wrecks."

In addition, horses are a self-renewing technology. Two tractors do not easily become three. George Rupp, a pioneer breeder of Belgians, humorously echoes this sentiment in his query: “When will they make a tractor that can furnish the manure for farm fields and produce a baby tractor every spring?”

Horses also offer companionship to their human counterparts. When working with horses you are intimately partnered with another living presence. As Wright says, “No one develops a rapport with a rototiller or tractor!”

Aden Freeman, born in 1930, has spent a lifetime working with horses. “I have been a farmer all my life and I have learned many skills,” he says. “I have used horses for a living as my only source of power. You have no idea of the commitment needed between the driver and team. Through the years if it hadn’t been for horses I don’t think I would be where I am today…I am not a wealthy man, but because I am a farmer I simply know who I am and what I feel. I wouldn’t have it any other way. Yes, I’m glad I am a farmer.” Horses help build communication skills and provide physical fitness for their owners. In other words, horses create healthy people.

Wright says, “It is our belief that no farm can consider themselves serious about sustainability if they rely on the tractor or some other internal combustion machine as their primary on-farm power source.” Animals are essential to a healthy, sustainable farm. As Charlie Pinney of the UK states, “replacing tractors with horses would enable farms to significantly reduce their fossil energy use. Growers who have already made the switch report reduced soil compaction, increased yields, and improved harvesting times.”

From work animals at the core of the agricultural, logging, and road building industries, among others, to companions used in sport and recreation, the horse plays a significant role in Canada's heritage. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives

Traditional Equipment in Use Today

Small-scale agriculturalist Tony McQuail has been farming with horses for a number of years and is a founding member of the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario. McQuail believes we need to redesign our society so that most of what we need to live can be created with energy from the food we grow. Trained in holistic management methodologies, McQuail solves many problems using only horse power. Holistic management was developed by Allan Savory, a wildlife and ranch biologist in Africa who created a program to help farmers establish a clear holistic goal and then use the farm’s resources to move toward the goal while being ecologically sustainable.

To illustrate this, a number of winters ago, McQuail had an issue with road access to his farm due to higher than average snowfall. He tried to use his clunky, old, gas-guzzling snow blower but the machine failed to accomplish the task. With the help of a local Mennonite friend, McQuail found a solution to the snow problem in a horse-power snow scoop.

Today, farming with horse power is experiencing a resurgence in popularity due to an increasing awareness of the detrimental impact of machinery on the environment. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

Teaching Farms and the Return of Horse Power

In response to this ecological crisis, small-scale teaching farms are sprouting up throughout Canada and the world, and sustainable farming practices are becoming more and more popular as people see the negative effects of industrialization on their families, communities, and the ecosystem.

Alberta’s Thompson Small Farm and its sister organization, The New Farmer School, were created out of the belief that “a return to a healthy, localized system of mixed farming using natural inputs is one of the fundamental steps we must take if we are to restore the health of human and natural communities on this planet and live sustainably.”

Wright believes that now is the time to “re-adopt the abandoned elements that worked, to re-embrace and to put back into practice the simple yet elegant systems with their track records of centuries.” The goal of these farms is to serve as an example of an alternative way to live that sustains local and global communities. To this end, Thompson Small Farm and The New Farmer School use animal power for as many tasks as possible.

The New Farmer School offers a number of courses such as the Work Horse Orientation Clinic. Through these courses, Wright hopes “to reacquaint folks with the working horse, to re-establish the working horse in our collective consciousness.” He views the work horse as the best option for achieving sustainability and energy independence, a necessary alternative that will assist us in severing our dependence on non-renewable resources and the damaging technologies associated with them.

There are a number of organizations, magazines, and other teaching tools to help beginner teamsters learn how to safely handle and farm with draft horses. The Draft Horse Connection, a quarterly journal in publication for over 17 years, also strives to keep the living tradition of Canadian heritage horse farming alive. Their magazine and DVDs are useful forums to preserve the knowledge of older generation teamsters, which can be handed down and shared with the younger generation.

Draft horses supply the living horse power that could help mankind move forward into an ecologically sustainable future. Photo courtesy of Soul of Canada

The Future of Horse Power

The mechanization of agriculture has created environmental problems that are difficult to overcome. Methods used in the industrial production of food alone have caused havoc to the land and the economy. Soil erosion, the abundance of pesticides in the ecosystem, and the overuse of antibiotics, genetically modified crops, and petroleum power sources are cumulative problems for both humans and the natural systems that support us. Many people, scientists and economists included, believe that humanity must return to past methods in order to restore the balance.

Can we help ourselves by reintroducing the working horse of the past into our future lifestyle? There are indications that this is already happening in agriculture, forestry, and other industries. The flourishing tourism industry has prompted the return of horse-drawn trolleys and carriages, which are again commonplace in historic areas and on many big city streets. The uses for draft animals are limited mostly by the imagination of people, and horses are doing amazing things, some traditional and others less so. The production and use of draft horses is, once more, a viable and growing business.

The future is already calling to the gentle giants to supply the living horse power that will help mankind move forward into an ecologically sustainable future.

For more information, please visit Soul of Canada.

Main Photo: Courtesy of Glenbow Archives - Horse-drawn binders not only cut crops but also bound them into small bundles. As agricultural technology grew, so too did the need for horsepower.