By Kevan Garecki

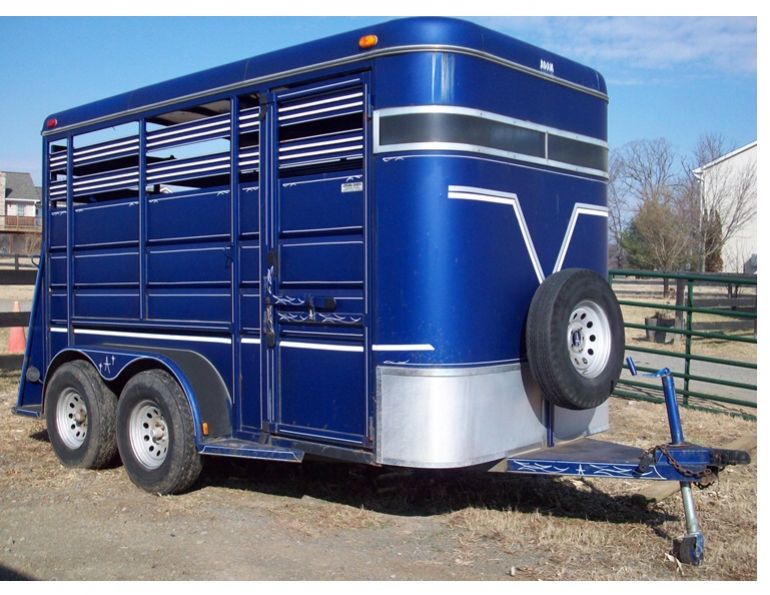

Horse trailer choices are almost as broad as truck options. While your specific trailering needs (e.g. how many horses you'll be hauling at any one time, size of the horses, typical hauling duration, etc.) will obviously impact your choice of horse trailer, the horses' safety and comfort should always be your primary concern when considering the following trailer options...

A straight haul trailer allows the horse to feel more secure as they are facing in the direction of travel. The ramp reduces strain on the tendons and ligaments and non-slip footing offers stable traction. Photo © Jebulon/Wikimedia Commons

Angle-haul vs. Straight-haul

Angle-haul trailers permit more horses to be put into a smaller space than conventional straight-haul designs. But if angle-haul trailers were so good, professional carriers would use them exclusively. So, why don’t we? Simply put, horses standing at an angle to the direction of travel are less secure (contrary to what the makers would have us believe), are put at higher risk for post-trip complications (particularly over longer distances), and lack the headroom which offers a measure of security to claustrophobic travelers. Additionally, angle-haul trailers with mangers at the head position may offer us more room to stow gear, but prevent the horse from lowering his head in transit, inviting shipping fever.

Step-up vs. Ramp

Ramps can reduce the stress on tendons and joints often associated with loading/unloading incidents. On the other hand, step-ups are easier to manage and most horses can certainly handle the hop needed to enter them. I have witnessed more injuries resulting from negotiating a step-up than those encountered on ramps. Ramps should have non-slip footing, and a longer ramp offers a gentler incline which is safer for the horse.

Bumper-pull vs. Gooseneck

Bumper-pull (Receiver) Hitches: The only bumper-pull hitches with sufficient capabilities to safely tow a loaded horse trailer are Class IV and V “receiver” models. A receiver hitch is installed onto the tow vehicle and accepts a hitch “head” into a two to two-and-a-half inch square tube. There are two types of hitch heads – weight-carrying and weight-distributing – both of which are designed to fit into the receiver hitch.

Photo: © BLW/Wikimedia Commons

Choose a head that will allow your trailer to ride level, and is rated for the weight. The average two-horse straight-haul can easily weigh over 5500 pounds (2500 kilograms) when loaded, and some steel three-horse angle-hauls can reach nearly 10,000 pounds (4600 kilograms) by the time horses are in, water tanks are filled, and tack/feed is on board. The hitch should be rated for at least ten percent above the maximum weight you plan on pulling. Most light trucks with factory towing packages include a Class IV receiver, which is rated for anywhere from 7000 to 9000 pounds of trailer weight, and 900 to 1000 pounds of tongue weight. This class of hitch is suitable for up to a three-horse trailer with a fully loaded weight of no more than 9000 pounds. For larger trailers, or for an added measure of security, a Class V hitch is commonly rated for weights up to 12,000 pounds and can accept up to 1000 pounds of hitch or tongue weight.

It’s important to differentiate between trailer weight (total weight of the trailer, including its full load) and hitch weight (weight bearing down directly onto the ball on the hitch head). Ideally, the hitch weight is roughly ten percent of the loaded trailer weight, but a weight-distributing, or “equalizer” head, when properly hooked up, distributes equal portions of the hitch weight between the front axle of the tow vehicle and the trailer axles. This arrangement has the distinct benefit of making for increased control between trailer and tow vehicle, while decreasing the wear on both the hitch itself and the rear axle of the tow vehicle. It also improves the ride of both units, meaning you don’t get jostled around as much and neither do the horses.

While gooseneck trailers offer several advantages over bumper-pull or receiver trailers, such as better weight distribution and easier turning capability when backing, they take up the majority of the truck bed and usually come with a higher price tag. Photos © BLW/Wikimedia Commons

Gooseneck Hitches: Gooseneck trailers have significant advantages over bumper-pulls. Simply because of where they connect to the tow vehicle, a gooseneck will track behind the truck more easily, can be turned more sharply when backing, provides better weight distribution, is more stable on the highway, and inherently provides a better ride for the horses. There are some sacrifices though. The majority of the truck bed/box is taken up with a gooseneck, thanks to the ball hitch mounted in the floor. It is still possible to use the area underneath the gooseneck for hay or tack storage, but take care to ensure the hitch and gooseneck will not strike anything packed beneath it. Price is another consideration. The average receiver hitch can cost between $700 to $800 when professionally installed (which every new hitch should be), while the average gooseneck hitch installation will likely cost in excess of $1500.

Braking Systems

By design, virtually every horse trailer must have two functional braking systems: a “service” brake that is applied every time the driver steps on the brake pedal, and an emergency brake that is automatically applied in case of separation. It is illegal to operate a trailer that requires brakes if both systems are not fully operational.

Installing brake controllers into a tow vehicle that does not already have them can be convoluted and difficult for those unfamiliar with the process. I highly recommend referring any brake issue or installation to a qualified professional at a reputable shop.

The best brake controllers to use are “proportional,” meaning that they apply the trailer brakes according to the braking of the tow vehicle. This is one of those areas where quality shines; get the best controller you can afford and take the time to set it up properly. Most digital models are sophisticated enough to allow the driver to “set it and forget it.” The common variable is the “gain control,” which allows the driver to adjust the amount of current to the trailer brakes when stopping. Slight adjustment may be needed to ensure both truck and trailer brakes work together to stop the vehicle safely and smoothly.

Main photo: ©jdj150/Fickr