By Margaret Evans

Cairo — The Beginning

Walid is worried. His donkey Marzouk is in terrible pain. He had rolled in his bedding and injured his side. Now the injury has festered and abscessed and it is clear that pulling the cart loaded with tools and other goods through the dusty streets of Cairo is agonizing.

But 31-year-old Walid must work to earn money to feed his wife and three children. He can’t afford to take any time off. Just yesterday a local vet had said that Marzouk needed an expensive operation. How can Walid afford that? He can barely put food on the table!

He desperately needs an answer. Then he remembers the clinic, the one they call the Brooke…

When Walid walked into the veterinary facilities, he entered a world of equine care and support beyond his dreams. But he had no idea that the origins of the Brooke had begun 75 years ago right in his home town of Cairo.

Dorothy Brooke, the wife of a British army major general, visited Egypt in 1930. She was horrified to see the appalling condition of ex-cavalry horses working on the streets of the capital. The horses had served British, American, and Australian forces during World War I and were sold after the war ended. But they had entered a life of crippling labour. They were pitiful walking skeletons.

Dorothy returned to England. But she was unable to shake off the memory of those suffering horses. She exposed their plight and raised enough money to buy 5000 animals and give them veterinary care. But many had to be humanely put down. In 1934 the experience inspired her to start the “Old War Horse Memorial Hospital” in Cairo with a promise of free veterinary care for all the city’s horses, mules, and donkeys.

This year the organization, now known as the Brooke Hospital for Animals, celebrates its 75th anniversary as the world’s biggest welfare charity for working equines. Today it reaches 700,000 animals annually. Brooke teams work not only in Egypt but also in Jordan, Israel, Palestine, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Guatemala. Its principles haven’t changed: free veterinary care for equines and education for owners and their families.

The problems, though, are immense and often repeated throughout the countries where the Brooke is working: extreme poverty, cultural practices that inflict harm to animals, and lack of animal husbandry knowledge that constantly puts animals at risk. By extension, a suffering animal unable to work puts a family at risk of increased poverty and possibly starvation.

“If an owner doesn’t know how to look after his animal it will inevitably fall into poor condition and become less productive,” said Joy Prichard, Brooke’s head of animal welfare and research. She added that less productivity leads to less care and the vicious circle can lead to animals becoming ill or dying which puts the owner’s livelihood at risk.

In Egypt, the Brooke has 27 mobile vet teams and seven permanent clinics based in Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor, Edfu, Aswan, Mersah Matrouh, and the Nile Delta reaching 130,000 animals a year.

“The poverty of people pushes them to choose to feed cattle and buffaloes more than equines,” explained Hesham Mohamed Morsy, community mobile clinic team leader in Edfu. “They also don’t treat problems or use wrong traditional treatments as they are cheaper. Poverty also makes owners put young equines to work and older animals work for long hours. They never stop working their animals even when they are injured or diseased.”

That had been Walid’s problem. When Marzouk was examined by the Brooke, the vet could see that he had rolled on an object concealed in dirty bedding. He told Walid that they could treat the donkey without surgery and nurse him back to health at no cost. But Marzouk would need to be in the clinic for several weeks.

“When the owners trust us, they usually start acting gratefully and they keep asking for more information about their animal’s care,” said Morsy.

While Walid was relieved that Marzouk would be treated, he agonized about how he was going to work. Then a friend lent him a donkey. He was so grateful. He vowed to follow the Brooke’s advice on donkey management and never neglect his animal’s needs again.

Chandni, a pinto mare in India, is examined and given fluids by a Brooke veterinarian after collapsing due to dehydration. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

India and Kenya — Education

Hazrat lives in Ghazaibad in India. He had just bought a pinto mare called Chandni when she suddenly collapsed. “My mare suddenly started sweating like somebody poured buckets of water on her,” said Hazrat. “She collapsed and now she’s unconscious!”

Hazrat calls the Brooke team in the area. Dr. Shikha examines Chandni and says that she is suffering from dehydration and is too weak to drink. He immediately starts her on fluid therapy. Chandni responds and an hour later she struggles to her feet.

The Brooke team tells Hazrat to keep her cool for a few more days, give her saline drinking water, and add salt to her feed.

Chandni, a pinto mare in India, is examined and given fluids by a Brooke veterinarian after collapsing due to dehydration. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

Hazrat’s call for help was typical of many owners in India where the Brooke has 19 mobile vet teams and a growing network of Community Animal Health Workers reaching 100,000 animals a year. Health workers are local residents trained by the Brooke in animal welfare. They provide a vital role supporting the mobile teams and connecting to the community.

“The Brooke team has identified owners who are… learning better skills and named them as ‘Ashwamitra’ (friend of horse),” explained Dr. Shikha Jain, veterinary officer in DEWU Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. “These are equine owners who are sensitized to animal welfare, and also have a rapport among other owners. These Ashwamitra are sharing their knowledge and spreading the Brooke’s message.”

Getting that message out demands innovative and new approaches. “Over the past two years our teams in India have developed participatory tools,” said Chief Executive Mike Baker, “Activities such as ‘If I was a horse/donkey’ and ‘welfare practice gap analysis’ put the animal at the very centre. Groups of owners analyze their situations and identify the need for improvements. (With) ‘animal body mapping,’ staff draw an outline of a horse on the ground then use coloured paints to show where and how an animal can be injured.”

Chandni recovered and her owner, Hazrat, is given instructions to keep her hydrated. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

The Brooke’s message is also targeted at children who play a vital role in animal care in all developing countries. “Children are very much involved in feeding, watering, and taking their animals to the forest for grazing,” said Jain. “Our team regularly organizes art competitions for the children and rallies to enhance their compassion toward equines.”

Thousands of kilometres away in Kenya, that same theme is at the heart of the Brooke-sponsored “donkey care clubs.” Donkeys are widely overworked, overloaded, beaten, and slashed by their owners. It has been a long-standing Brooke policy to reach the young generation, instill the values of humane care, and end crippling cultural practices. The clubs are operated at schools where pupils learn about donkey welfare through song, poetry, dance, and drama, then perform these arts in local communities. Many children proudly wear T-shirts sporting a donkey and the words “Punda ni rafiki” meaning “a donkey is a friend.”

Since 2001 the Brooke has reached a wider audience by funding the Kenya Network for Dissemination of Agricultural Technologies (KENDAT), a multimedia format using billboards, schools, welfare field days, and the media. One radio program called “Mtunze Punda Akutunze” (Kiswahili for “look after your donkey and she will look after you”) has captured Kenyans’ imaginations. They tune in weekly to learn about donkey care. The Brooke teams are now seeing fewer donkeys with wounds and there is even an increase in owners taking nutritious packed lunches for their donkeys’ midday meals!

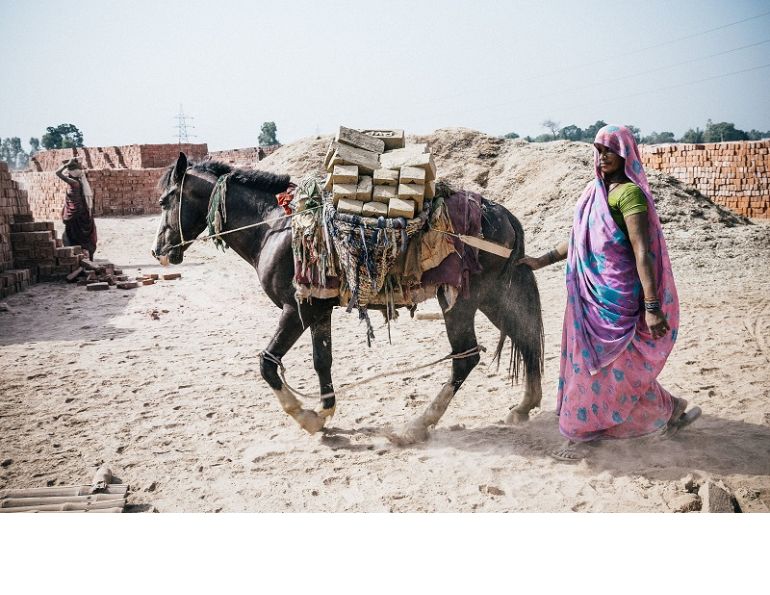

Mithu, a Pakistani brick kiln donkey, collapsed from exhaustion after being overloaded with unbaked bricks. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

Pakistan — Changing Behaviour

Every day, Mohammad Nazir loads his donkey Mithu with 90 kilograms of unbaked bricks. He leads him up a steep bank to the Basti Labar brick kiln in Multan, Pakistan. They make the trip almost 25 times every day and, by sunset, the little donkey has transported three tonnes of cargo. Mohammad is only paid a penny for every ten bricks transported so the more he takes the more money he makes.

Consequently, Mohammad begins increasing the number of bricks per trip. Despite the hellish heat, there is no time to stop for food or water. Until, one day, Mithu’s legs begin to buckle and he collapses from exhaustion.

Mithu, a Pakistani brick kiln donkey, collapsed from exhaustion after being overloaded with unbaked bricks. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

In a country that celebrates the healthiest polo ponies, some of the industries are borne on the backs of the poorest brick kiln donkeys. The Brooke is the largest animal welfare organization in Pakistan and operates in eight urban centres: Lahore, Peshawar, Multan, Mardan, Gujranwala, Faisalabad, Jaffrabad, and Karachi. It reaches some 280,000 animals through 31 mobile teams, community animal health programs, seven field clinics, and 92 treatment points. Since 1991, the Brooke estimates it has helped to support the livelihoods of over 1.5 million people.

Mithu receives aid from a mobile Brooke unit. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

“One of our biggest challenges is the use of long-standing traditional practices,” said Asad Rana, veterinary officer in Multan. “My team is convinced that behaviour change is the most challenging part of our job. We emphasize just how important these hard working animals are. (They) are what keep them from plunging deeper into poverty.”

When Mithu collapsed, Mohammad pulled the bricks off him and contacted the nearest Brooke mobile team. They spent hours treating the donkey for dehydration, wounds, and exhaustion. Brooke vet Dr. Rab Nawaz spent several one-on-one sessions with Mohammad instructing him in proper feeding, resting, and watering as well as first aid and the dangers of overloading. It took Mithu a month to recover.

Mohammad became a changed man, vowing never to overload Mithu again. “As the Brooke showed me, it won’t increase my income or Mithu’s health or productivity.”

His owner, Mohammad, has vowed never to overload Mithu again, and received instruction from Brooke on proper feeding, resting, watering, and first aid. Photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals

Ethiopia — Positive Relationships

Three days a week, 32-year-old Tagese Alemheyu makes a grueling walk with his mule from his rural home in southern Ethiopia. He lashes grain sacks weighing 120 kilograms to the animal’s back and, at three AM, he sets off to market in Hossana, 33 kilometres away. The harsh, hilly journey takes seven hours and they arrive exhausted. His mule stands without food or water while Tagese tries to sell the grain, called “teff,” that is used to make the sour flat-bread “injera.” If he’s lucky, he’ll make $5 profit for the day’s sales. Then, man and mule must walk all the way home.

Their journey is duplicated by hundreds of poor farmers who rely on a tiny bit of money to feed and clothe their families and put their children through school. Their animals are not only the lifeline against starvation but also the catalyst by which a man is respected in the village. The people of Ethiopian culture frown on a jobless man.

Ethiopia is one of Africa’s poorest countries. In a land ravaged by drought, it is cruelly ironic that its economy for 74.2 million people revolves around agriculture. After China, Ethiopia has the second highest density of working equine animals in the world with over one million horses and three million donkeys. Over 85 percent of Ethiopians live in rural areas and possibly up to 98 percent own one donkey.

Many owners do not have the most basic of animal husbandry skills and thousands of horses and donkeys suffer from malnutrition, heat stress, chronic lameness, pressure sores, and exhaustion from the brutally heavy loads of grain they carry. In addition trypanosomiasis, a disease transmitted by the tsetse fly, causes agonizing pain and is fatal if not treated.

The journey to the grain markets is especially brutal for all equines. Animals walk for six hours with staggering loads. Exhausted, dehydrated, and with sores and open wounds from the ropes wrapped around their bodies, they stand in the hot sun while owners try to sell the produce. At the end of the day they repeat the arduous journey home. Many collapse, face down in the dirt, unable to move one more step. Not knowing any better, some owners think they are just resting.

The Brooke’s presence in Ethiopia began in 2006 and focused on three locations in Gondor, Harraghae, and the southern region with headquarters in Addis Ababa. Last year they helped 38,500 animals.

“Our biggest challenge is the deeply embedded attitudes using harmful traditional practices,” said Alemayehu Hailemariam, vet service coordinator in Hossana. “Such practices involve burning or firing, spreading ash on wounds, inserting toxic powders in the nose and eye, etc. What we set out to do on a daily basis is change people’s attitudes and culture but it is a lengthy process.”

Effective animal care has a vital spill-over impact among poor families. “We conduct vaccination campaigns to reduce mortality of donkeys, horses, and mules,” said Hailemariam. “If a family loses a donkey to an epidemic, the female members of the household will often bear the burden. (Without the donkey) she has to carry things by herself for long hours.”

Despite enormous difficulties, the Brooke teams are building meaningful relations with local communities. Owners have a lot of respect for the vets.

“We sometimes get frustrated when we see mistreated animals but we are careful not to show this to the owners as we do not want them to shy away from us,” explained Hailemariam. “Some owners are surprised to see that we are so concerned about their donkeys and horses. Our passion for the animals helps us win (their) trust. Owners often bring coffee, milk, and cereals to us to show their appreciation.”

“Some owners have told us that nobody has ever bothered about their horses and donkeys before,” said Melese Negash, animal health field worker in Butajira where the Brooke works with the Gari (cart) horse owners. “Gaining the people’s respect helps facilitate our work. They are very cooperative and willing to participate in our activities, which is important if we are to bring about positive change.”

In that change lies a brighter future for working equines. “The Brooke’s research program has been very successful in investigating welfare issues such as dehydration and pain in donkeys,” said Baker. “Research findings are used directly by our field staff.”

In the constant need to reach more animals over a wider geographical spread, the Brooke partners with many other organizations including non-government organizations (NGOs), universities, and governments. “Partner organizations often have a better understanding of the local context,” Baker added, emphasizing that an NGO with a long-term presence can get up to speed more quickly, helping to deliver veterinary care.

Seventy-five years ago, the passion of one lady started a movement to help the horses in Cairo. Today, the Brooke’s five-year goal is to reach two million equines in the world’s poorest countries. They are getting there, one animal and one grateful owner at a time.

For more information on the Brooke, visit www.thebrooke.org.

Main photo: Brooke Hospital for Animals - Walid and his donkey Marzouk, who recovered from an infected injury thanks to Brooke.