By Lindsay Grice

Q As someone who has worked with various horse professionals over the years, attended many clinics, and owns a library full of books, I realize that there are lots of different opinions about how horses think. How does one separate fact from fiction, in your opinion?

A In the information age, blogs and online forums provide a buffet of answers to the questions horse owners have as they try to communicate with their 1000 pound, non-verbal partners. The processes of horse training and management can be puzzling. In the horse world, where fiction and fact often collide, how do we know how horses really think, feel, and learn?

“If we could talk to the animals, learn their languages...maybe take an animal degree...” (Dr. Doolittle)

When riding and showing horses, we’re always solving puzzles such as how to resolve a behavioural problem, figure out the source of a gait abnormality, or how to teach and refine skills. When it comes to figuring out the best approach to these puzzles, I’d rather get right to the facts than muck around with speculation.

So, what solution has the best track record of success with multiple horses, time after time? Is there research to back up the theory? Is it a lasting solution or a quick fix?

I approach training on the basis of behavioural science which can help explain how horses think and learn.

We’ll never know what it’s like to be a horse, but there is a wealth of evidence pointing to the way horses are wired...and they’re not wired like humans!

So how do we know what we know?

Proven Research

One of the things I love about teaching equine behaviour is studying the research that’s been conducted on behalf of horses. Studies of hundreds of horses confirm that horses learn by operant conditioning (i.e. trial and error, pressure and release).

|

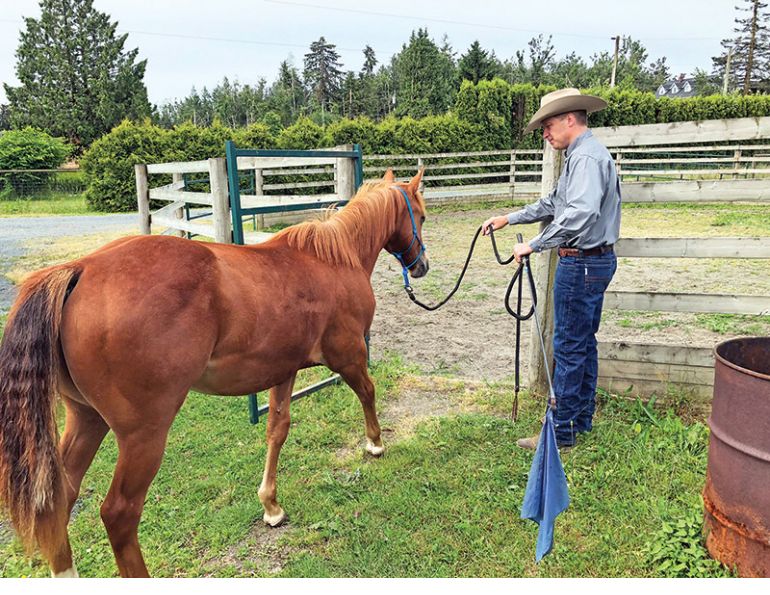

Photo: Mary R. Vogt - As prey animals, horses find comfort and safety in the presence of a herd. |

We’ve learned what motivates them, what scares them, and what they actually see, hear, and smell.

Equipment is used to measure heart rate and stress hormone levels during various training and handling practices. Many of the findings verify what those of us who have trained many, many horses have concluded intuitively.

However, based on what we now know through science, I’ve changed my approach in some areas over the years, turning my back on some stubborn traditions.

The evidence of the horse’s brain

By comparing the anatomy of the human brain to that of the equine brain, we see that horses have a relatively small area devoted to reasoning and higher thought processes such as analyzing and strategizing. Social grazing animals don’t need humans’ ability to speculate (What if?), plan (Next time I will...), or analyze emotion (I really overreacted...).

Instead, horses have a large region devoted to coordination and learning by doing, as well as a photographic memory when it comes to recalling dangerous situations (albeit without the human capacity to analyze those memories).

The evidence of survival as a prey animal

What motivates a grazing prey animal? The instinct to flee perceived danger, to seek comfort in the safety of the herd, and the ability to roam, graze, and procreate, all are strong motivating factors for a horse.

How differently the horse trainer and dog trainer must approach their teaching! Prey animals don’t need strategy or logic. They need to follow the leader, escape entrapment, and react quickly.

It seems to me that the most efficient and humane way for me to solve my horse puzzles is to set my human reasoning and emotions aside, take an honest look at the facts, and think like a horse!

Main article photo: Robin Duncan Photography - Your instructor should be able to help you separate fact from fiction when it comes to horse psychology.

This article originally appeared in the April 2012 issue of Canadian Horse Journal.